Introduction

With the increasing complexity of surgical procedures, acquiring of advanced skills has become essential in surgical training.1,2 Despite the increased complexity, the length of the surgical training program has remained unchanged over the past several decades. Innovative ways to improve the learning curve of surgical residents are required. This study aims to describe our experience with structured educational video-sessions to improve the learning curve of surgical residents.

One of the procedures introduced early in the surgical training program is laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Although the procedure itself is standardized, providing targeted feedback and setting specific learning goals is challenging due to the lack of objective and procedure-specific evaluation criteria.3 Additionally, learning opportunities for residents are often deprioritized during surgery due to time constraints in the operative room (OR).4 Currently, the Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS) is used to assess the learning curve of surgical residents in the Netherlands.5 However, the objectivity of this method is questionable, and its reproducibility is limited.6,7 Although OSATS evaluate general surgical skills, such as tissue handling and instrument use, it is not procedure specific. As a result, it is not well suited for providing structured feedback on the different aspects of a specific procedure, such as transection of the cystic duct and artery in laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Different innovations to improve procedure specific feedback for surgical residents are promising. First, the use of procedure specific tools such as Competency Assessment Tools (CATs). They have been shown to be effective in assessing progress in various surgical procedures2,8,9 and are strongly associated to outcome.8 CATs were originally developed to measure the technical quality of surgery in the context of surgical trials, but new research has shown CATs can also serve as valuable tools for educational purposes.8,9 Second, video sessions have been proven effective in non-surgical educational settings,8 particularly in simulation-based education.10 During video session a recorded procedure is reviewed with a group of peers and an expert. Research suggests that incorporating videos into educational sessions facilitates personalized feedback that is directly linked to the visualization of specific actions, contributing to a greater sense of competence.8 The results of this non-surgical research support our hypothesis that video-based education, combined with procedure-specific CATs could be highly beneficial for surgical residents and could enhance their laparoscopic learning curve.

The primary objective of this pilot study was to evaluate the perceived value, assessed by the residents, of structured educational video sessions on laparoscopic cholecystectomies in the surgical training program. We hypothesized that structured video sessions, when implemented in the surgical training program, would be of value to surgical residents and result in perceived improvement of operative skills, a greater sense of confidence, and earlier independence in performing a laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Methods

In this pilot study, all seven surgical residents from the Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital (CWZ) were included. CWZ is a teaching hospital providing secondary care. All residents performed laparoscopic cholecystectomies, under the direct supervision of an attending surgeon or as primary surgeon, depending on their level of training. All procedures were performed in an elective setting for symptomatic gallstone disease. Procedures performed on patients younger than 18 years, conversions to open cholecystectomy and incomplete videos due to technical failure, were excluded. Procedures were recorded and anonymized. Anonymized operative videos were uploaded to a digital platform (Incision Care). Incision Care is a secure website where users can upload and share their recordings, as well as watch and review those of other surgical residents. Each surgical resident submitted two to three videos performing a laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Structured educational video sessions

Monthly video sessions were organized over a six-month period. All seven surgical residents and one senior surgeon participated in these sessions. At each session two videos, from two different residents, were discussed. Each video started with a brief oral introduction of the patient by the resident, along with strengths and difficulties experienced during the procedure. Based on the recorded video, residents discussed various surgical actions, strategies and problems. The senior surgeon participated as moderator, intervening in the discussion only when deemed necessary. The goal of the sessions was to address well-performed actions and pitfalls, and to provide each resident with constructive feedback on their surgical skills. Based on the constructive feedback, residents were given individual learning objectives for the next procedure. Each session lasted approximately two hours. To guide the residents in discussing all relevant items, an Artificial Intelligence (AI)-assisted video analysis and a CAT were used.

Competency assessment tool

The CAT was developed by two surgical residents and a senior surgeon based on previously developed CATs for surgical procedures11 and previously described surgical steps for laparoscopic cholecystectomy.9 The CAT divides the procedure into five steps: abdominal cavity access, critical view of safety, cystic duct & artery transection, resection of gallbladder and gallbladder and trocar removal. Each step was evaluated based on four domains, including exposure, execution, errors and adverse events and end product quality (supplementary material, figure 1). CATs were scored for each video by all the residents and the senior surgeon. Discrepancies in CAT scores between individuals were used to start discussion on relevant items.

AI-assisted video-analysis

In addition, all video submissions to Incision Care were analyzed using AI that was available on the Incision platform. The AI, which extracted several parameters: instrument pathways, instrument overshooting, bleeding and gallbladder injury. During the video sessions, these parameters were used as a supplement to the residents in discussing the surgical video.

Questionnaire

The primary outcome measure was the residents’ experienced value —‘perceived operative skills, risk awareness, confidence and independence in laparoscopic cholecystectomy procedure and self-reflection’— using a questionnaire administered at six months. The questionnaire was based on the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM),12,13 which is a validated tool commonly used to assess the learning environment based on six different subjects.13 From the original 50 items of the DREEM questionnaire, items that were not applicable were excluded (supplementary material, figure 2). Additional relevant questions were added and formed a questionnaire consisting of 53 items. Responses were documented using a Likert scale, ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). A total score was determined using all items (53) of the questionnaire. Items worded negatively required recoding prior to calculating the total scores. The calculation interpretation of the total score was determined analog to the original DREEM questionnaire14 (table 1).

Secondary outcome measures included residents’ perception on the teaching method, procedure-specific topics and developing their academic skills (figure 2).

Statistical analysis

The ordinal data derived from the ‘experienced value’ questionnaire were analyzed using descriptive statistics and presented as mean and standard deviation. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS® (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA; Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0).

Results

During a six-month period, all seven residents participated in six structured educational video sessions and completed the questionnaire after the last training session. In total, twelve laparoscopic cholecystectomies performed by seven residents were uploaded and evaluated. Three residents had 1 to 3 years of resident training experience, and four residents had 4 to 6 years of resident training experience.

Primary outcome parameters

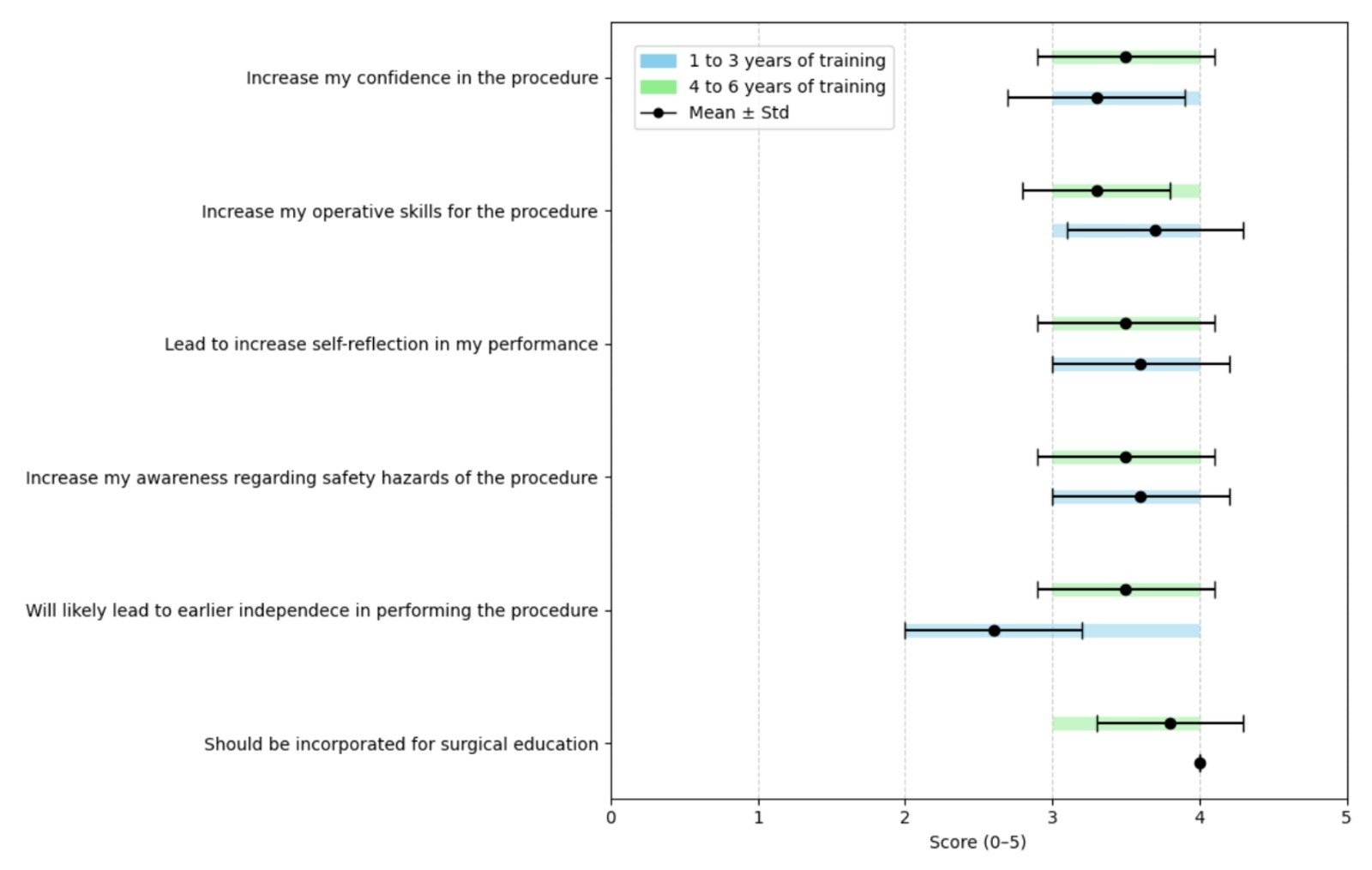

After six months residents experienced improved operative skills (mean 3.4 (SD 0.5)) and enhanced self-reflection (mean 3.4 (SD 0.5)) for laparoscopic cholecystectomies (figure 1). Additionally, residents reported an elevated level of awareness concerning safety hazards during the procedure (mean 3.6 (SD 0.5)) and an increase in their confidence in performing the procedure (mean 3.4 (SD 0.5)). There was a strong consensus among residents that the video sessions should be incorporated in the surgical training program (mean 3.9 (SD 0.4)). They agree that it could potentially lead to earlier independence in performing the procedure (mean 3.1 (SD 0.7)).

Residents with 1 to 3 years of training perceived a more notable enhancement in their operative skills (mean 3.7 (SD 0.6)) and elevated levels of self-reflection in performance (mean 3.6 (SD 0.6). In contrast, residents with 4 to 6 years of training reported scores of (mean 3.3 (SD 0.5)) and (mean 3.5 (SD 0.6)), respectively.

Secondary outcome parameters

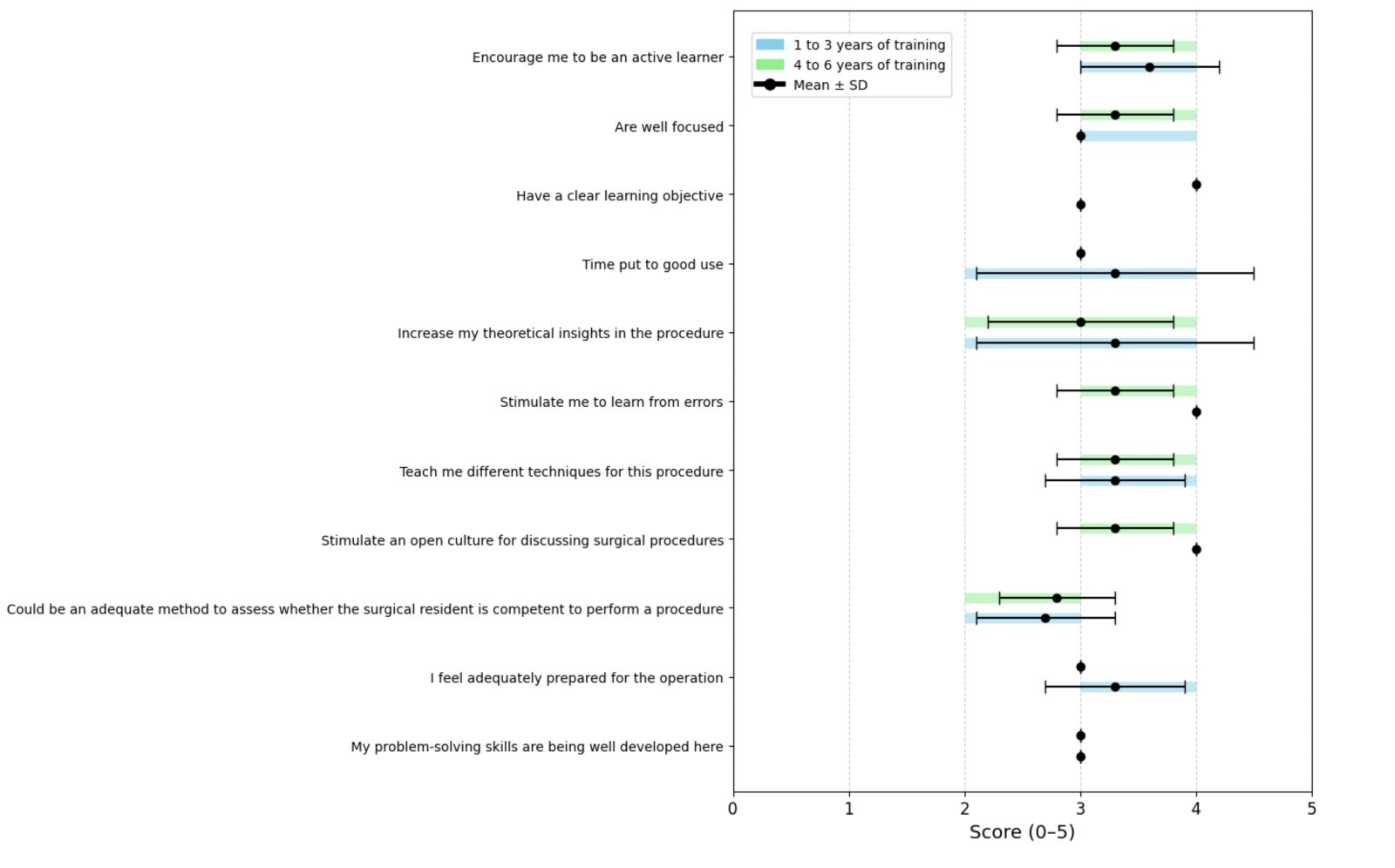

Video sessions were scored effective in encouraging active learning among the residents (mean 3.4 (SD 0.5)) and stimulated them to learn from errors (mean 3.6 (SD 0.5)) (figure 2). The learning objective of the video sessions were clear (mean 3 (SD 0)), and the sessions were well focused (mean 3.1 (SD 0.4)). The residents further reported an open culture for discussing surgical problems during the video sessions (mean 3.6 (SD 0.5)). Additionally, residents agreed that time invested in the video sessions was time put to good use (mean 3.0 (SD 0.8)) and that the sessions could serve as an adequate method to assess whether the surgical resident is competent to perform a procedure (mean 2.7 (SD 0.5)).

Residents with 1 to 3 years of training placed a higher value on the time allocated to the sessions (mean 3.3 (SD 1.2)), compared to residents with 4 to 6 years of training (mean 2.8 (SD 0.5)). During the video session the less experienced residents were more encouraged to engage as active learners compared to the more experienced (mean 3.6 (SD 0.6) vs. 3.3 (SD 0.5)) and were more stimulated to learn from errors (mean 4 (SD 0) vs. 3.3 (SD 0.5)).

Total score outcomes

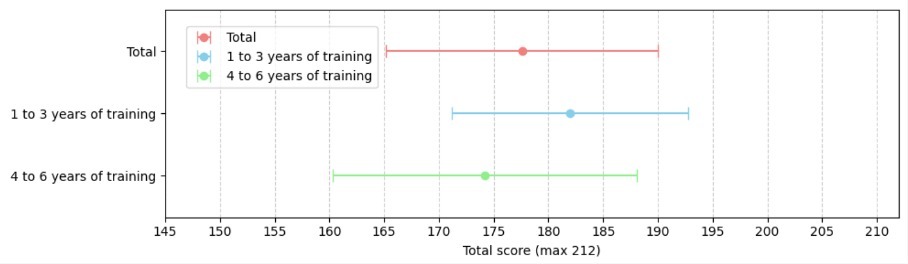

The mean scores on the DREEM Questionnaire of all residents combined was 177.6 (SD 12.4) (figure 3) indicating an excellent educational intervention, independent of their years of training.

Discussion

This pilot study demonstrates that surgical residents perceive structured educational video-sessions supported by CATs as an excellent educational intervention in the context of laparoscopic cholecystectomy training. Participants reported improvements in operative skills, increased awareness of procedural risks, greater confidence, and enhanced self-reflection. Junior residents appeared to benefit most from this educational approach.

This study represents the first initiative to integrate educational video-sessions with a procedure-specific CATs within the context of surgical training for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The combined approach facilitates the delivery of structured, objective, and personalized feedback that is directly tied to operative performance, rather than relying on generalized or subjective evaluations.

The study design promoted active learning and peer-to-peer discussion within a safe and supportive learning environment, thereby stimulating self-reflection and critical analysis of both individual and peer surgical techniques. The educational intervention proved to be both practical and feasible when implemented in existing surgical training curricula. The further refinement and standardization of this training method holds potential for broader application across multiple laparoscopic procedures. Our experience suggests suitability for integration into training programs in other surgical disciplines, such as urology and gynecology.

Additionally, the integration of structured video-based assessments supported by CATs offers promising implications for professional development and competency evaluation. Recorded procedures could serve as objective evidence of progression within a resident’s surgical portfolio, allowing both trainees and supervisors to longitudinally monitor technical growth throughout the program. Furthermore, the accumulation of surgical video data has the potential to facilitate the development of semi-automated or AI-assisted assessment tools. These tools may enhance the objectivity, efficiency, and scalability of surgical performance evaluation in the future.

This pilot study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the sample size was limited, comprising only seven surgical residents from a single teaching hospital. This study was intended to assess feasibility and perceived educational value of the intervention, but this restricts the generalizability of the findings.

Second, the primary outcome measures were based on self-reported data, which are inherently subjective and susceptible to biases such as social desirability and recall bias. To objectively determine the efficacy of the educational intervention in improving surgical skills, future studies should incorporate video-based assessments using pre- and post-intervention CAT scores for laparoscopic cholecystectomy, ideally with a larger sample size and across multiple training centers.

Finally, the CAT utilized in this study had not undergone formal validation by experts. However, the tool was created using a format of validated CATs and used content from previous studies in which surgical steps of laparoscopic cholecystectomy were determined.8 In addition, the lack of validation was not critical for the current study, as CAT scores were not used as primary outcome measures, but only as a tool to start discussion during the video sessions. For future research in which CAT scores are analyzed, systematic and scientifically rigorous validation of the tool will be essential.

Despite these limitations, positive feedback from participants and consistent trends in perceived learning gains suggest that structured educational video-sessions supported by objective assessment tools holds promise as an effective, practical adjunct to traditional surgical training methods. The promising outcomes observed in this initial study led to the subsequent implementation of the training program in five additional teaching hospitals across the Netherlands, suggesting potential scalability. Future research should focus on investigating the implementation of the video sessions on larger scale and the correlation of CAT-scores with clinical outcomes. Assigning senior residents a more facilitative role, such as moderating discussion during the sessions, should be considered to ensure continued engagement and educational value.

Conclusion

With the increasing complexity of surgical procedures, surgical education faces new challenges. There is an increasing demand for innovative approaches to optimize the learning curve of surgical residents. Structured educational video-sessions supported by procedure-specific CATs are perceived as valuable by surgical residents and holds promise as an effective surgical training method. Future studies should assess objective skill improvement and explore the implementation on larger and broader scale across surgical specialties.