Introduction

In the United Kingdom (UK), on 26th March 2020, COVID-19 lockdown measures legally came into force. This lockdown period was extended for months, with some measures relieved on 10th May and further local lockdowns in July. The subsequent lockdowns from 31st October and 6th January were followed by gradual easing of restrictions.1 During the first wave, hospital beds were needed for COVID-19 patients, therefore, elective operations had to be cancelled, whilst others were conducted in a private hospital setting, which may have negatively impacted surgical training.

The UK General Medical Council (GMC), highlighted in their National Training Survey (NTS) that the COVID-19 outbreak caused major disruption to formal training, with 75% of trainees and trainers claiming that teaching received or provided was disrupted.2 81% of trainees and 87% of trainers felt that the COVID-19 pandemic reduced opportunities required to gain the required curriculum competencies. Worldwide, surgical trainees had their training opportunities cancelled as many non-urgent elective surgeries were suspended.3

The breast services in the UK continued to function as per the pre-COVID-19 outbreak in terms of outpatient activities. Elective admissions for surgery were carried out in the private sector with the majority of cases performed as day case procedures or with short-term hospital stays. In the Royal Free NHS Foundation Trust, all cases were done in private hospitals; the Wellington Hospital (HCA Healthcare), the Princess Grace Hospital (HCA Healthcare) and King Edgware Private Hospitals. To minimise major complications, complex reconstructive procedures were restricted. A regional multidisciplinary meeting was set up to determine the merit cases that would require complex surgery. Oncoplastic level one or two breast surgeries were allowed on the discretion of individual surgeons.

In the UK, the majority of graduates from the general surgical programme undergo sub-speciality fellowship training for one year, specialising in breast oncoplastic surgery since the introduction of the Training Interface Group (TIG) fellowship. Our hospital is one of the centres in the UK that offers this fellowship. In addition to that, we also offer non-TIG fellowships for international graduates. The training component of non-TIG fellows is funded by their service commitment. The entry criteria of non-TIG fellows is highly variable in the UK, unlike the UK TIG fellows in which they are nationally regulated and funded.

Unlike the USA, postgraduate breast training for general surgical graduates in the UK is very different. In the UK and perhaps most European countries, breast fellowships focus heavily on plastic training of the breast, hence the postgraduate trainees in the UK are jointly trained by breast and plastic surgeons. Whereas in the USA, the breast fellowships have a strong emphasis on the oncological aspect of the breast. Therefore our study looking at the effect of COVID-19 on “plastic surgical” training of breast trainees is novel and unique.

To assess the effect of the COVID-19 outbreak on UK-based breast trainees and its implication on their post-graduate practice after becoming independent surgeons, we retrospectively analysed trainees’ experiences before, during and after COVID-19. As a control, we took the same cohort of trainees in the same period a year before the COVID-19 outbreak. It is difficult to control all variables for this form of study as the COVID-19 event happened unexpectedly. To manage all biases and variables, we restricted our scope of study to one individual consultant trainer since he had similar cohorts of trainees. Trainees supervised by this consultant were either from the interface group (TIG fellows) or were post-completion of certificate training (CCT) from Greece. Both groups of trainees either from pre-COVID-19 or COVID-19 had similar clinical experiences prior to entering the training programme, thus, we tried to match our major variable of this study equally.

In this study, we concluded that both sets of trainees received a similar exposure to different techniques of oncoplastic procedures, however the volume of exposure was higher in the pre-COVID-19 period. We noted that the exposure of the COVID-19 cohort with reconstructive surgery was compromised. Both cohorts graduated from the programme after one year and obtained their respective consultant appointments. We also followed these cohorts of trainees by reviewing their practice after graduation from the programme. Minor differences were noted on their practice following the graduation of breast sub-speciality training. In fact, the post-CCT trainee during the COVID-19 period passed his European Board of Breast Surgery examination with a distinction.

Materials and Methods

A comparison of the quarter from March to June 2019 (pre-COVID-19 pandemic) with the quarter from March to June 2020 (during the outbreak) was conducted. Similar months were chosen to avoid any seasonal variation and the cohorts of trainees were similar. One consultant was chosen to control the variability of different consultant training methods. The trainees in these cohorts were comparable: one National TIG fellow and one post-Certificate of Completion of Training (CCT) Greek-trained senior fellow (identical).

All patients who underwent surgical treatment with a diagnosis of primary breast cancer or non-cancer between March 2019 and June 2019 at the Royal Free Hospital were included in this retrospective observational cohort study. For a comparison, all patients who underwent surgical treatment with a diagnosis of primary breast cancer between March 2020 and June 2022 at all private London hospitals were included.

The planned approach and related factors for each patient were discussed in both pre- and post-operative multidisciplinary meetings.

Clinicopathological data included in the prespecified case report form was collected from our hospital’s patient record system and the operational record system. Data extraction was performed by a senior fellow in surgery. All information was de-identified, and the information was kept in a coded database.

A number of parameters were recorded pre-COVID-19 and during the pandemic: the number of cancer cases, non-cancer and reconstructive and day cases, tumour characteristics, any technical procedures performed by trainees (e.g., drains), type of surgery (mastectomy, and breast-conserving surgery removal and axillary surgery), type of procedure (round block, lateral, vertical and Grissoti’s Advancement Flap).

Cosmetic outcomes were also evaluated at the 1-year follow-up by all included patients and by the treating surgeons. The evaluation was performed using a Harvard scale for cosmetic outcomes.4 Each time point assessment was completed by the fellows using the four-tier Harvard Scale (Excellent, Good, Fair, Poor). The results were registered for patients’ and surgeons’ evaluations, separately.

Complications were recorded for each patient according to the Clavien–Dindo classification system and the presence of complications on the breast cancer-affected side and the contralateral side, separately.

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) was used for statistical analysis. P values should be interpreted as level of evidence against each null hypothesis tested rather than as significant or not according to a cut-off. We made no adjustments for multiple testing.

Results

Comparison of trainees’ experience pre-COVID-19 and during outbreak

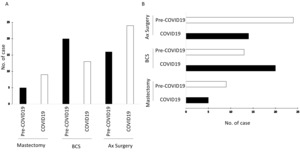

During the COVID-19 outbreak, cosmetic and benign cancer removal surgeries were cancelled or postponed. Elective risk-reducing cases were also cancelled and rescheduled. Only breast cancer cases with involvement of level one and two oncoplastic procedures were performed. The number of non-cancer and reconstructive cases reduced by 100% over the first wave of outbreak. This significantly decreased our trainees’ operative experiences during the months of March, April and May 2020. For the cancer caseload requiring breast surgery, there was a 1.5-fold increase (Figure 1a) in comparison to the same period a year prior to the COVID-19 outbreak. No benign or reconstructive cases were performed during the outbreak period (Figure 1b). The phenotypes for cancer cases diagnosed during the COVID-19 period tended to be larger in size and with biologically unfavourable characteristics (Table 1). This reflected the oncologists’ reduced favour towards offering any neo-adjuvant chemotherapy during the pandemic period.

Comparison of mastectomy and Breast Conserving Surgery

Not all breast oncologic procedures were affected in the same manner; our own case volumes during and after the COVID-19 period demonstrated an increase in mastectomy without immediate reconstruction and a decrease in wide local excision with level one or two oncoplastic intervention (Figure 2). The most affected training opportunity was the prophylactic mastectomy since no cases of this surgery were recorded in this period. In addition, we experienced a decrease in immediate reconstruction after breast surgery, with the greatest reduction in cases utilizing autologous tissue.

During the outbreak, there was a 12% reduction in caseload requiring surgical interventions (either straight forward mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery). This may represent the problem with accessibility to diagnostic procedures during the outbreak. Greater requirement for axillary surgery during the outbreak period was merely due to the larger and unfavourable phenotypes of cancers in comparison to the same period a year before that (Table 1).

Activities of oncoplastic procedures during the outbreak

Upon recommendations from the Association of Breast Surgeons (ABS), UK, the number of mastectomy cases rose by 50% and axillary surgery cases by 66.7% (Figure 2a). There was a 30% reduction in breast-conserving surgery cases (Figure 2a). Of those cases, it would be of interest to determine whether the trainees were the primary surgeons under supervision of the consultant: almost 97.2% cases during the pandemic were the trainees acting as the primary surgeon in comparison to 88.6% in the same calendar period prior to the outbreak (Figure 2b). All cases were fully supervised by the consultant, whereby the consultant scrubbed up as a first assistant.

Surprisingly, day cases reduced by 17.9% and drain use decreased by 50% during the outbreak (Table 2). The reduction of day cases likely resulted from the pandemic situation. It is of this trainer’s practice that the use of a drain is limited - even with mastectomy or axillary lymph node dissection. Special operative techniques of an oncologic surgeon allow for them to negate the use of a drain. Only two cases during the pre-COVID-19 period required drain usage in comparison to one case during the pandemic.

Surgical trainees experience during the outbreak

In terms of oncoplastic breast surgeries, oncoplastic surgical cases were performed by trainees with a consultant scrubbed, providing feedback at the end of the procedure. There was no difference noted between pre- and during pandemic periods. The only difference is that during pre-COVID the trainees performed fewer axillary procedures in comparison to the outbreak period. This is probably consultants willing to allow the trainees to do more, knowing that the COVID-19 outbreak could impact the training opportunities.

In terms of oncoplastic procedures, the major bulk of work was round block mammoplasties. A large reduction of round block procedures was performed during the COVID-19 period, almost half of those recorded during the pre-COVID-19 period (Figure 3a). The rest of oncoplastic procedures did not have any statistically significant difference. The fellows’ logbook also reported similar findings (Figure 3b).

To see whether the outbreak affected the time trainees spent in theatre, we collected the hours spent for educational purpose in operative and non-operative sessions. All non-operative activities were unaffected by COVID-19 in the UK breast service. The trainees’ activities involved in the clinic, oncoplastic multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings, oncological MDT meetings or non-cancer MDT meetings were not affected by COVID-19 (data not shown). Each TIG fellow was required to attend one session of symptomatic clinic, an oncology follow-up clinic, and one plastic clinic per week. For non-TIG fellows, the attendance requirements for symptomatic and oncological fellow clinics were at least 4-5 times higher than TIG fellows due to the fact that their salaries were 100% funded by the NHS trust, therefore these trainees did need to fulfil their service commitments.

The operative experience (qualified by hours spent in theatre) for TIG fellows was almost halved for trainees during the COVID-19 period (Figure 4). This is because all plastic theatres were closed during the COVID-19 period. The majority of TIG fellows spent their time with the oncological surgeons. There was no difference in terms of time spent in theatre for non-TIG fellows either before or during COVID-19. Unfortunately, our non-TIG fellows spent one sixth less of their time in operative training as they were only allocated to one oncological surgeon (during the fellowship), whereas the TIG fellows were allocated to at least 2 oncological surgeons and 2 plastic surgeons. In the UK, TIG fellowships were funded by the Joint Committee on Surgical Training (JCST) Breast Interface Fellowship. The job plan or the training model for non-TIG fellows was extremely variable within the UK trust and regulated by employing hospital trusts.

Surgical complication rates over the pandemic

During the COVID-19 pandemic period, there was a small increase in seroma and haematoma complications, with a 2.7% difference (Table 3). These are relatively minor complications associated with oncoplastic intervention.

To determine cosmetic outcome, we used Harvard scoring to assess both cohorts. 1.1% more cosmetic outcomes were ‘Excellent’ pre-COVID-19 but overall cosmetic outcomes did not differ significantly. We are aware that physician-assessed cosmetic outcome using the traditional four-point Harvard Scale is highly variable and influenced by evaluator factors. It is important to note that the aim of this study is not to assess the cosmetic outcomes, but to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 on the experiences of trainees.

Comparison outcome of trainees after graduation from the programme

All trainees became consultants: the TIG fellow became a substantive NHS consultant, the Greek fellow working pre-COVID became a locum NHS consultant and the fellow working during the outbreak became a substantive consultant in Greece.

The trainees from both time periods obtained consultant posts and were able to perform level one and two oncoplastic procedures, implant-base reconstructions, and autologous reconstructions (Table 4) – the practices are similar.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic represents an unprecedented challenge to medical care, therefore there is a need to develop a flexible model for patient care. In the UK, the Association of Breast Surgeons (ABS), UK, published specific recommendations.5 These recommendations are to optimise treatment timing, allocation of limited resource, limiting transmissibility through infection reduction measures and implementing increased safety precautions for healthcare workers. The extent to which these recommendations were practised was however left to the discretion of the individual regional MDT.

The Royal Free NHS Foundation Trust is a centre for plastic and reconstructive surgery with 7 breast consultant led-units and over 700 new breast cancer cases per year. It also hosts a regional plastic unit as well. Our trainees experienced a decrease in immediate reconstruction after breast surgery, especially with cases involving autologous tissue. Very similar experiences were also reported by others.6,7 In our institution, this did not significantly affect the caseload requirement for the trainees’ programme as we were fortunate to have been at high-volume regional centres and had met most minimum operative requirements well before the pandemic.

We reported that the number of cancer surgery cases increased during the pandemic period. This may be due to the cancellation of non-cancer cases, therefore allowing patients to receive surgery more quickly with a shorter waiting list. There was almost a complete cessation of non-cancer activities, such as benign and risk-reducing cases. More mastectomy cases were conducted during the pandemic, and most of these cases were without an immediate reconstruction. Fewer breast-conserving and more axillary lymph node surgeries was due to the aggressive phenotypes of cancer requiring surgery during the pandemic (Table 1). We noted that neoadjuvant chemotherapy cases were halted due to the fears of the effects of the pandemic on chemotherapy treatment as well as reduced service provision. Similar observation was reported by others.8,9 Whether this limited use of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy impacted or will impact the disease outcomes is beyond the scope of examination of this study. Such results have been previously characterised by other groups in different countries.10–12 Variation in the results may reflect the differences in national policies for the pandemic.13

As with many reports, the pandemic did affect the training of trainees.14 In terms of exposure to oncoplastic procedures, we reported that fewer mammoplasties were performed during the COVID-19 period. More challenging axillary surgeries were conducted during the pandemic period due to the more aggressive phenotypes of cancer that required surgical intervention. One could argue that those trained during the pandemic received a different exposure with a bias towards difficult and challenging oncological surgery. Therefore the experiences obtained by the trainees was different to those trained pre- or post-pandemic. Those trained pre-COVID were exposed to more oncoplastic and plastic procedures.

Unlike other subspeciality training, breast surgery represents a high operative volume with a minimal risk for significant utilization of healthcare resources and hospital capacity. This may imply that most breast fellows currently in training may be able to continue their involvement in operative cases, in the event of a further prolonged COVID-19 pandemic. Similar experiences were noted by breast surgery fellows of other institutions in the UK and the USA with high volumes.15,16 The decreased operative exposure is comparable to those of other sub-specialties, which similarly demonstrated overall reduced caseloads and logged procedure numbers for trainees. For example, the TIG fellow trained before the pandemic had nearly 400 operative hours over the 3-month period, whereas the TIG fellow during the pandemic period was only able to obtain 75% of that time. In comparison, non-TIG fellows, who are allocated one oncological surgeon in the training model, were only able to obtain less than 100 operative hours over the 3-month period both pre- or during the pandemic.

Judging the capacity of the trainees after graduating from training programme, either TIG or non-TIG fellows, both cohorts of trainees became competent consultant surgeons. The cohorts have similar surgical practices after graduation, suggesting that the operative exposure afforded to the non-TIG fellow is sufficient to train an adequate oncoplastic surgeon. Our high-volume unit has offered an extra advantage to our TIG fellows. It has been noted that non-TIG cohorts were post-CCT fellows, and also Greek board-certified general surgeons, prior to their embarkment to our training programme. We are aware the limitation of our study is that we are not directly scrutinising the practice of our graduates. We are pleased to report all our graduates maintain a safe practice and are also able to carry out all oncoplastic and reconstructive procedures that are expected from a new generation of oncoplastic breast consultants.

We recognise that current non-TIG fellows have largely variable backgrounds of training, especially since the UK’s exit from the European Union (EU). The majority of non-EU trainees applying for non-TIG fellow appointments might not have the same level experience as EU post-CCT graduates, therefore current operative training hours may not be sufficient for particular training backgrounds. Our training model might be not be applicable to these trainees. However, our experience with Greek post-CCT fellows indicate that our current Royal Free training model is adequate to provide them with ample “operative hours” to achieve a competency level that is similar to the TIG fellows.

In terms of non-operative activities in breast sub-speciality, it was minimally affected by the pandemic. All breast clinics for triple assessment or oncology were running as usual. All the adjuvant specialities associated with breast service during pandemic were also functioning as pre-pandemic. The trainees’ experience of the non-operative environment was not affected adversely. During the pandemic, there were changes on clinical practice resulting in hybrid working and virtual attendance.17

Conclusion

Despite the difficulties faced with the COVID-19 pandemic, and the reduction in teaching opportunities, all trainees developed the competencies required to become consultants and were able to perform the same post-consultant practices. The pandemic may have affected the volume of caseloads or hours spent in theatre, however training was not compromised. The trainees that graduated before and after COVID-19 have equal ability to maintain a similar surgical practice.

Authors’ contributions

Formal Analysis: Amelia Snook (Supporting). Investigation: Eleftherios Sfakianakis (Supporting). Writing – review & editing: P Tan (Lead).

Conception and design of study: ES and PHT

Acquisition of data: AS and ES

Analysis and/or interpretation of data: AS, ES and PHT

Drafting the manuscript: AS, ES and PHT

Revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content: AS, ES and PHT

Approval of the version of the manuscript to be submitted: AS, ES and PHT

_the_number_of_cancer_cases_pre-covid-19_(black_bar)_and_during_covid-19_(white_bar)._b).png)

_therapeutic_mammoplasties_march-june_2019_(black_bars)_and_march-june_2020_(white_bars).png)

_the_number_of_cancer_cases_pre-covid-19_(black_bar)_and_during_covid-19_(white_bar)._b).png)

_therapeutic_mammoplasties_march-june_2019_(black_bars)_and_march-june_2020_(white_bars).png)