Background

The medical community has long acknowledged the significance of developing cultural competency throughout the entirety of medical education. ‘Cultural competency’ is defined by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as “the ability to honor and respect the beliefs, languages, interpersonal styles, and behaviors of individuals and families receiving services, as well as staff members who are providing such services. Cultural competence is a dynamic, ongoing developmental process that requires a long-term commitment and is achieved over time.”1 The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) identifies cultural competency as a component of three out of the six core competencies, including patient care, professionalism, and interpersonal communication skills.2

Though the importance of cultivating cultural competency in medical education is widely understood, there is a general lacking of formalized curricula to address this need. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) notes criteria for cultural competency curricula, including consistent, integrated educational initiatives appropriate to the level of the learner and a clearly defined evaluation process, which may include student feedback for consideration of how the intervention may be improved in the future.3 This indicates that efforts to build cultural competency among students cannot be viewed as an “add-on” event and must take place longitudinally over the course of training. Further, because the diversity of the United States is ever-increasing,4 the intervention(s) must be dynamic and responsive to the changing needs of trainees and the feedback obtained from these learners.

Global health education programs within U.S. residency programs provide learners with the opportunity to explore an interest in global medicine while also developing the training necessary to recognize the social determinants of health encountered by locally and nationally underserved and populations.5 Most approaches to increasing global health exposure amongst U.S. trainees have primarily focused on in-person international electives6; however, logistical challenges, elective time, costs of travel and housing, and the recent travel restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic have presented significant barriers for implementing long-term global exposure into residency curricula.5 This has made it difficult for programs to provide adequate global health exposure throughout residency, including U.S. neurosurgical training programs. Ultimately, this indicates that most neurosurgical residents have limited exposure to how neurosurgical intervention is approached in resource-poor environments, educational tools that are also useful when practicing in local resource-limited settings or when treating patients who require recognition of the social determinants that are impacting their illness and subsequent treatment.6

Consideration of these barriers, particularly the restriction of travel due to COVID-19, reveals the need of neurosurgical residency programs to establish innovative time and resource-accessible opportunities for trainees to be exposed to both global health and global neurosurgery. With this in mind, UNC-CH Neurosurgery implemented a novel, virtual global case conference approach with the goals of (1) continuing to develop the department’s longstanding relationships with practices in Mauritania and Brazil and (2) to continue involving program residents in the field of global neurosurgery as means of fulfilling educational competencies put forth by the ACGME.

This study aims to elucidate resident perception of the conferences and to assess the educational applicability of these conferences through surveys administered to the resident physicians of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Department of Neurosurgery. The data collected outlines the benefits of these sessions and the barriers that impede resident participation.

Methods

Global Case Conference

The UNC-CH Neurosurgery Department global case conferences were established in 2019 with neurosurgical practices in both Mauritania and Brazil in-lieu of in-person travel due to COVID-19 pandemic travel restrictions. The conferences occurred during the regularly scheduled morning report times (7:30 - 8:00 am) for the UNC-CH Neurosurgery residency program on the third Wednesday of each month. The virtual sessions are in collaboration with UNC-CH Neurosurgery global partners in either Mauritania or Brazil via Webex, alternating monthly. All UNC neurosurgery residents were required to attend global conferences. The objectives of these global conferences were to continue developing longitudinal relationships with global partners while also meeting the following ACGME Competencies for UNC-CH Neurosurgery residents:

-

(IV.B.1e)(1a): “Residents must demonstrate competence in communicating effectively with physicians, other health professions, and health-related agencies.”2

-

(IV.B.1f):“Residents must demonstrate an awareness of and responsiveness to the larger context of health, including the social determinants of health, as well as the ability to call effectively on other resources to provide optimal care.”2

From the implementation of the conferences in 2019 to September of 2022, over 20 global conferences were held. The format of the sessions is as follows: a brief presentation of neurosurgical cases, including intraoperative video, photos, and scans, by a resident from either the UNC-CH or global partner institution followed by an open discussion from all conference participants, including both resident and faculty. The content covers a diverse array of cases, including surgical intervention for more common procedures, such as shunt insertion, as well as intervention for more complex and rare diagnoses. The discussion often encompasses differential diagnoses, surgical approach, and consideration of social and cultural factors that may impede or impact the treatment plan. In total, each conference is planned to take 30 minutes as to ensure suitability and sustainability in resident schedules. The case presentations are approximately 8-10 minutes in duration and the remaining time is allotted for discussion.

Surveys

This study was deemed exempt by the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board. Consecutively, a paper survey was distributed to all UNC Neurosurgery residents who attended conferences to assess the educational value and applicability of the global case conferences. The survey was also distributed electronically via Qualtrics to residents who were not in attendance at the meeting, as well as to the two chief residents who graduated from the program in 2021. Participation was voluntary. The survey included 17 questions, including Likert scale, with surrounding themes such as conference organization, participation, comfort level, and applicability to ACGME milestones. An open-response section was also included for residents to provide feedback and recommendations to improve the conferences in the future.

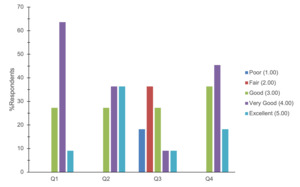

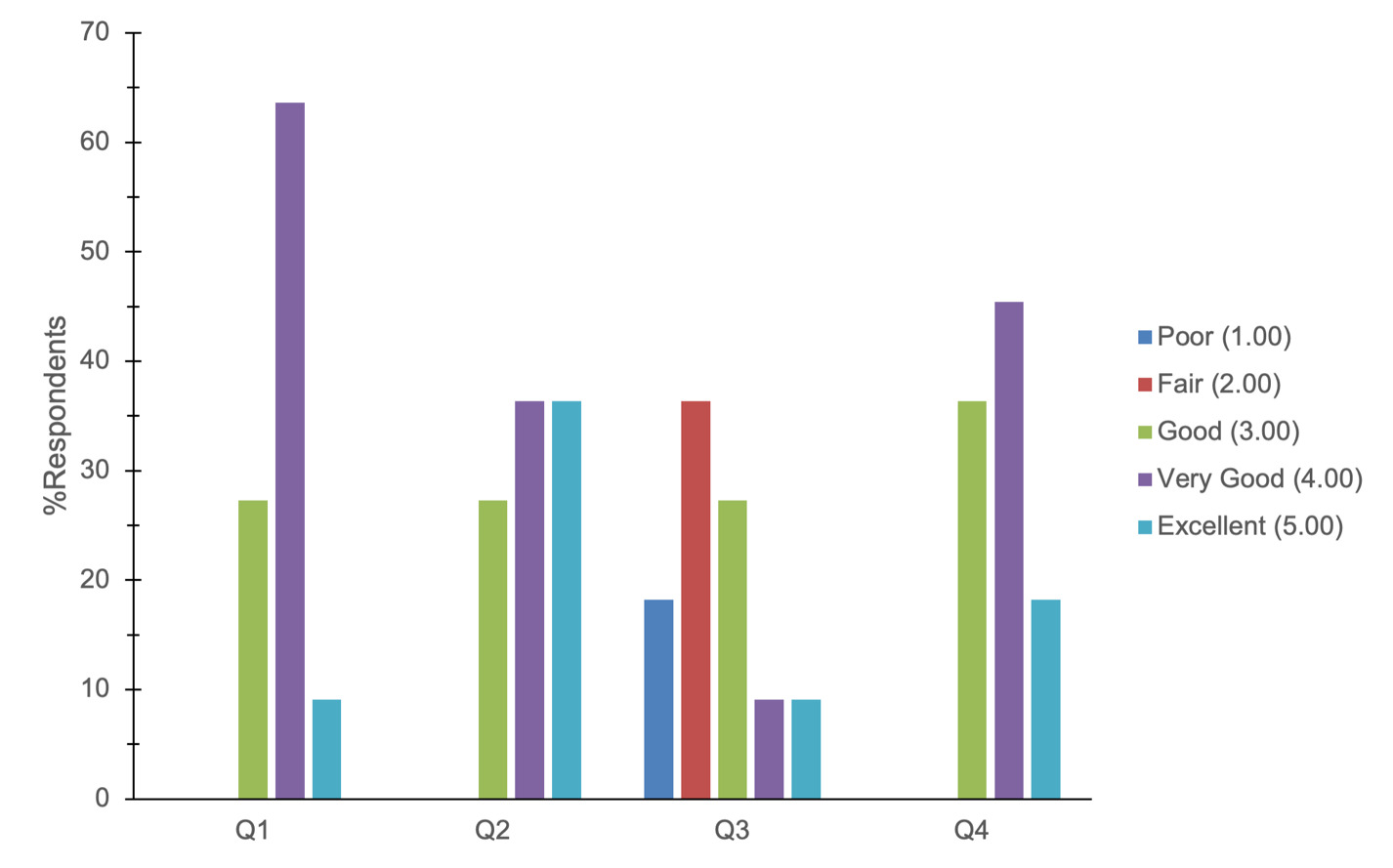

Grading scales were assigned to qualitative responses to allow for quantification of results. For questions 1-4, the following scale was applied: poor (1.00), fair (2.00), good (3.00), very good (4.00), and excellent (5.00). For questions 5-9, the following scale was applied: strongly disagree (1.00), disagree (2.00), neutral (3.00), agree (4.00), strongly agree (5.00). Responses were assessed using descriptive analysis on Microsoft Excel.

Results

The survey was distributed to a total of sixteen residents. Of the sixteen residents, eleven residents (69%) completed the survey and their responses were included in the analysis. Survey questions are shown in Table 1. As displayed in Table 1, participant mean responses to questions regarding case conference design, discussions, and quality were Q1 (3.82), Q2 (4.09), Q3 (2.55), Q4 (3.82). Questions 5-9 provide insight into respondents’ self-assessment and individual perceptions of case conferences [4.14, 4.14, 3.50, 3.80, 4.00]. ACGME Competencies were directly evaluated in questions 8 and 9. Short answer responses are displayed in Table 1.

Discussion

This survey aimed to evaluate the educational value and applicability of the monthly virtual global case conferences implemented as components of UNC Chapel Hill Neurosurgery Department’s global health initiative. The scheduled monthly mandatory conferences utilized a longitudinal framework integrated into the curriculum which provides residents with early and continuous opportunities to learn from residents and attendings who practice in resource-limited environments; this exposure is necessary to train culturally competent physicians capable of recognizing social determinants of health. The virtual nature of these conferences allowed residents to maintain this exposure while mitigating the costs, resources, and time-restrictions associated with in-person travel. It also allowed for global collaboration that would have otherwise been impossible due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

As displayed in Figure 1, most respondents reported that find the discussion during the conference to be good or very good (X = 3.82) and find the collaborative nature of the discussion to be very good or excellent (X = 4.09). This suggests that the discussions amongst residents and attendings in the U.S. and global partner institutions are worthwhile aspects of the conferences. When asked in an open-response question format what elements of the conferences are most valuable, three responses noted the collaborative discussion as the most beneficial component (Table 2). The overall quality of the sessions was rated to be good/very good (X = 3.82), which demonstrates that the conferences are well-run and organized, but suggests that there are areas that could be further improved to enhance the quality of the sessions.

The surveys also aimed to specifically address two of the core competencies put forth by the ACGME. Most participants reported that they were neutral, agreed, or strongly agreed that the conferences helped them to better notice and address social determinants of health and develop cultural humility (X = 3.80). Most respondents also reported that they agreed or strongly agreed that the conferences helped them grow their ability to effectively communicate with other healthcare providers (X = 4.00). This data suggests that the sessions offer useful educational tools for fulfilling these core competencies in a manner that is more accessible to learners than in-person, global travel.

While this novel global case conference structure can introduce residents to global health, it is subjected to its own challenges. To meet the objectives, this program requires participants to be engaged to truly foster an exchange of knowledge. However, the majority of respondents rated their comfort participating in the discussions as poor, fair, or good (X = 2.55). Most respondents reported that they agreed or strongly agreed that their contributions to the sessions are valued by other participants (X = 4.14); however, three individuals reported that they do not participate at all. This indicates that barriers to participation may be a factor limiting the overall educational value of the conferences. Further, one participant commented that it would be useful to have “More international participation, sometimes feels like a UNC department discussion” (Table 2), which suggests that physicians and residents from the international groups do not always participate equally. However, residents offered suggestions to increase participation such as designating a theme for conferences ahead of time and discussing broader topics that are applicable to both institutions.

The notable lower comfortability of participating in discussions from UNC-CH residents, as demonstrated by Figure 2, could be precipitated by language barriers and conference organization. Conference discussions were often structured to be led by attendings, which can limit resident participation if steps are not taken to actively engage the residents. Of note, one participant stated that it was: “Difficult to participate as a junior resident” (Table 2), which suggests that post graduate year may be related to level of resident participation in conference discussion. For future application, it would be beneficial to incorporate planned methods to involve residents at every level of their training.

Virtual learning environments can pose barriers to participation if technical issues ensue. It was noted that the conferences would be improved with, “Better internet access/IT support.” (Table 2), which is a common problem with virtual settings. These issues improved with each conference as both institutions became better acquainted with the Webex program, and virtual nature of the discussions; however, IT issues cannot always be avoided.

Two limiting factors of this study are the small sample size (n=16) and the response rate (69%). Though the sample population is small, this is not atypical considering neurosurgery residency programs are generally small in size. UNC-CH Neurosurgery accepts two residents each year, totaling in fourteen individuals for the seven-year residency program. The low response rate primarily resulted from lower voluntary participation from residents who were surveyed via Qualtrics. For future evaluation, this suggests that it may be useful to survey all participants in-person rather than electronically to encourage a higher response rate.

Though the objective of this survey was to assess the educational value of these global conferences for U.S. residents and their applicability to the ACGME competencies noted above, a future study may also survey international residents to evaluate their comfort participating in the discussion and their overall perception of the sessions. Though this study is largely descriptive in nature, this data lays the foundation for future, quantitative assessment of global case conference utility in addressing ACGME milestones in neurosurgery residency.

Conclusion

The creation of a required, virtual, monthly global conference has enhanced the UNC-CH Neurosurgery residency program by providing exposure to areas of global neurosurgery and offering tools to meet the educational competencies put forth by ACGME. We believe this conference structure enables residents to improve collaboration with international colleagues, communication skills, and cultural humility in a manner that is time-, resource-, and cost-accessible. Similar conferences can be implemented in other residency program curricula to promote the importance of these competencies across the field.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Department of Neurosurgery at UNC Chapel Hill School of Medicine for allowing us to collect this survey data.