Background

Pediatric trauma is the leading cause of death among children aged 1-14.1 However, the volume of pediatric trauma is low compared to adult trauma.2 This limits trainee and provider experience with the most acute pediatric traumatic injuries and with pediatric trauma procedures.3 Additionally, variation in age-specific vital signs,4,5 differences in age-specific medication dosing and instruments for procedures, and differences in acuity and mechanisms of injury make managing pediatric trauma unique.2 These educational needs and unique factors have led institutions to develop simulation programs for training providers.

Prior research demonstrated the efficacy of trauma simulations at improving teamwork, accuracy and speed of trauma surveys, overall comprehensiveness of pediatric trauma evaluations, and perceived quality and efficiency of care.6–8 Trauma simulations have also been shown to reduce the time to critical procedures.8 Prior research has analyzed simulations designed to educate providers on general trauma scenarios and components of the resuscitation9–12 while less research has emphasized methods to identify and target institution-specific knowledge gaps.

One method of identifying knowledge gaps is the needs assessment survey. This is the process of assessing training and education needs and aligning these identified needs with an educational curriculum.13 Despite utilization in other areas of medical education, a needs assessment survey for designing pediatric trauma scenarios has not been established or investigated. The objective of this study was to evaluate the results of a needs assessment survey aimed at understanding the areas perceived by members of the multidisciplinary pediatric trauma team as needing improvement during trauma resuscitations.

Methods

This study was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board (#23-2373) and declared exempt. Informed consent was obtained from participants electronically via the survey link.

Population and Survey Recruitment

A needs assessment survey was conducted at a single level 1 pediatric trauma center (PTC) from April 2024 to August 2024. The study institution is the only level 1 PTC in a seven-state catchment area, serving as a tertiary referral center for a diverse group of patients who experience traumatic mechanisms at all levels of acuity. Trauma team providers were recruited in the emergency department following all the highest-level trauma activations during the study period. Recruitment occurred via a QR code provided to the team on completion of the resuscitation, which linked to the needs assessment survey. Recruitment immediately following trauma activations ensured that all providers who typically participate in trauma resuscitations at our institution had the opportunity to respond to the survey. This includes physicians, advanced practice providers (APPs, i.e. Nurse Practitioners/Physician’s Associates), registered nurses (RNs), paramedics/emergency medical technicians, pharmacists, and respiratory therapists (RTs). Aside from indicating their role, responses were anonymous.

Survey Design

This novel pediatric trauma education needs assessment survey was designed by the simulation program team at the study institution. This team consists of a pediatric surgeon, emergency medicine physicians, an anesthesiologist, and a nurse who is the simulation department manager. The survey was reviewed by the nurse manager in the emergency department for approval prior to implementation. This group represents the multidisciplinary team that participates in the highest-level trauma activations at the study institution. The survey was designed to assess the domains of leadership, teamwork, and patient care goals. One of the study authors (SA) has formal training in survey methodology. The survey consisted of 21 questions including 18 closed-ended questions utilizing a Likert scale and two open-ended questions. Likert scale questions were either on a scale from 1-6 (1 indicating “completely disagree” to 6 indicating “completely agree”) or 1-4 (1 representing “goal was not met at all” or “roles were poorly understood” to 4 representing “goal was completely met” and “roles were very well understood and tasks completed”). The first question was the study consent. Consent was required for study enrollment. The full survey instrument can be found in the supplemental materials (SDC1).

Analysis

The types of providers and traumatic mechanisms are reported as a percentage of the total respondents. For analysis of Lickert scale questions, responses were dichotomized into “needs improvement” and “does not need improvement”. For the 6-point Likert scale, scores of > 4 were considered acceptable; for the 4-point Likert scale, scores of > 3 were considered acceptable. Analysis was performed to identify areas of the trauma resuscitation that need improvement. The free-text questions were analyzed using the 6-step method for analysis of qualitative data described by Braun and Clark.14 Theoretical thematic analysis was performed by coding responses to free-text questions using an open coding method. Responses to the free-text questions were not required to complete the survey.

Results

Study Participants and Trauma Mechanisms

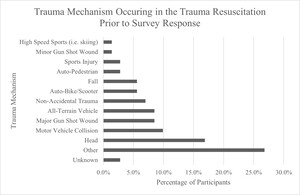

During the study period, there were 62 trauma activations, and 62 team members responded to the survey. However, three survey forms were blank and were excluded from final analysis, resulting in inclusion of 59 participants. Forty-four percent (26/59) were physicians, 22.0% (13/59) APPs, 16.9% (10/59) RNs; 5.1% (3/59) emergency medical technicians, paramedics, technicians; 1.7% (1/59) pharmacists, 10.2% (6/59) other, and 5.1% (3/59) missing (Figure 1). The trauma mechanisms in the resuscitation prior to the survey responses are described in Figure 2. The highest proportion of trauma mechanisms was described as other (26.8%), head (16.9%), motor vehicle collision (9.9%), major gunshot wound (8.5%), All-Terrain vehicle (8.5%), and non-accidental trauma (7.0%).

Areas of Trauma Resuscitations Identified as Needing Improvement by Respondents

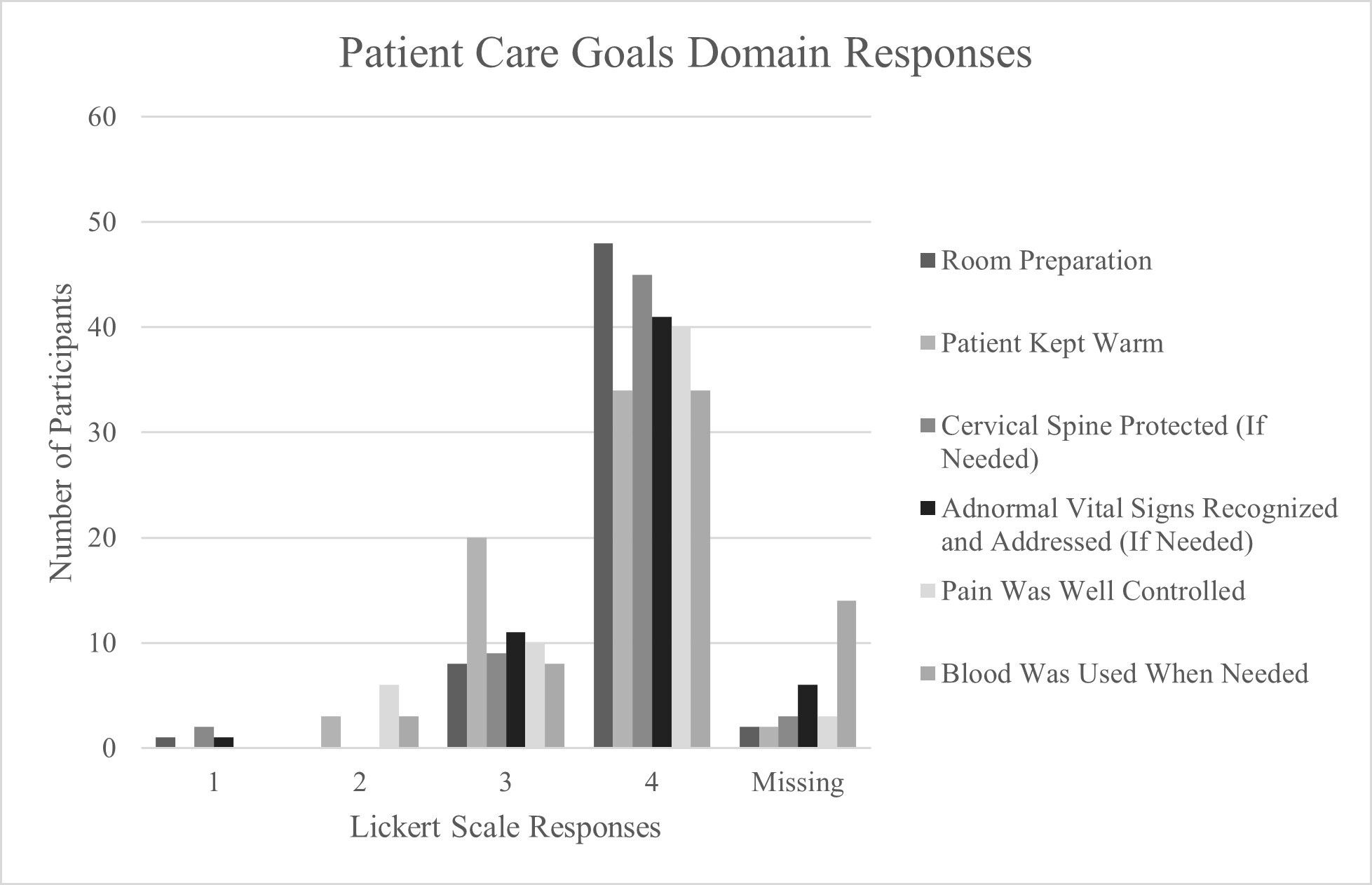

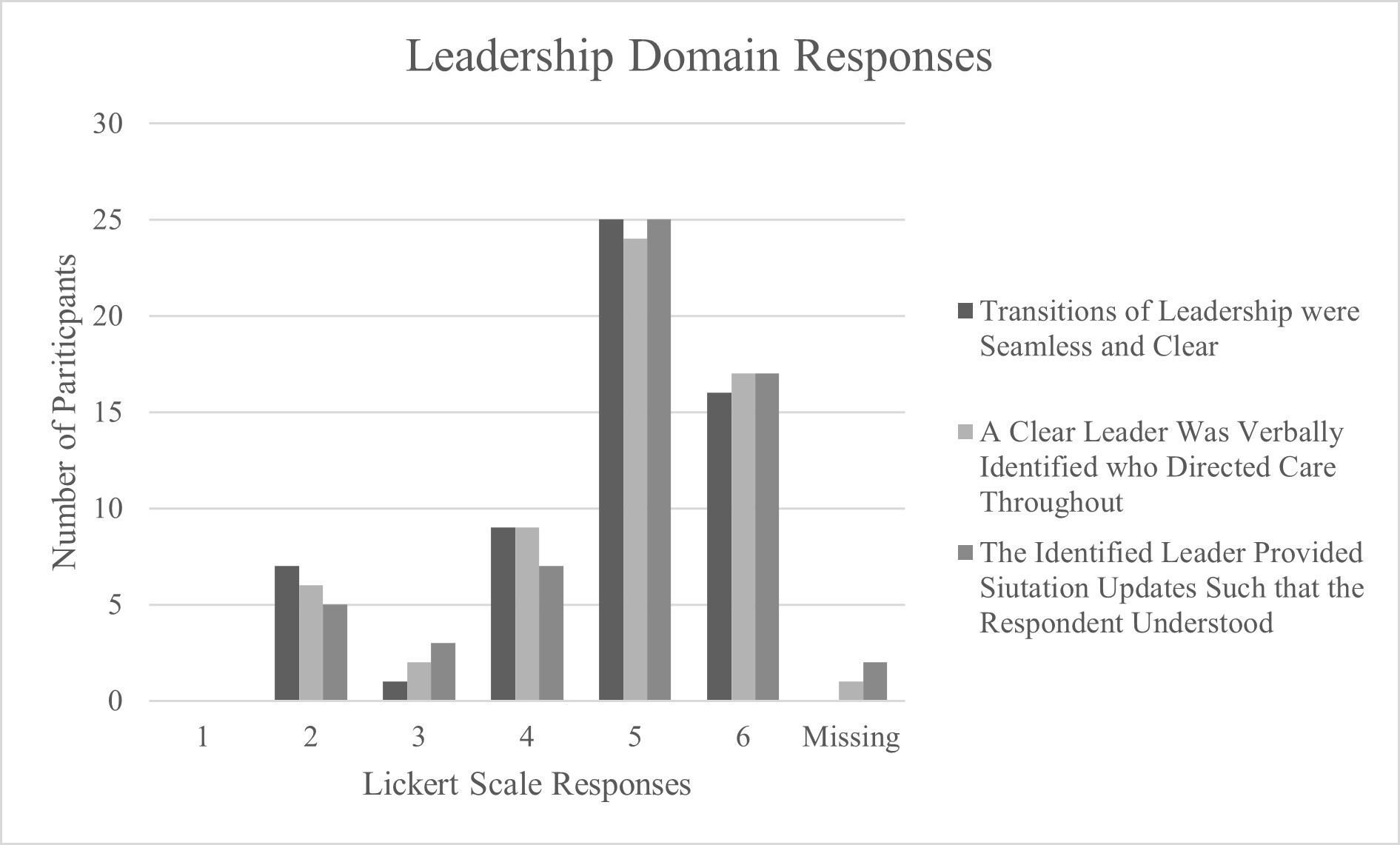

Overall, most reported none of the survey domains needed improvement (Figure 3-5). However, several of the leadership domains and some subdomains of teamwork and patient care goals had a relatively higher proportion of responses indicating a potential need for improvement. Within the leadership domain, relative areas identified for improvement were transitions of leadership (30.5%), identification of a clear leader who directed care throughout (28.8%), and the leader providing situation updates such that the participant was able to understand them (25.4%) (Figure 3). For the teamwork domain, whole team function and closed loop communication (25.4%) (Figure 4a) and roles being well assigned for the team as whole (35.5%) had a relatively higher proportion of responses identifying a need for improvement. This is approximately 19% higher than the proportion of participants who reported that team roles were well assigned for themselves (16.9%) (Figure 4b). Finally, the patient care goals with a relatively higher proportion of responses indicating a need for improvement were keeping the patient warm (39.0%) and pain control for the patient (27.1%) (Figure 5).

Thematic Analysis of Free-Text Reponses

Thirty-two percent (19/59) of participants provided free-text responses regarding transitions of leadership. Thirty-seven percent (22/59) of participants provided a free-text response regarding concerns about the trauma resuscitation preceding the survey or trauma resuscitations at the study institution in general. Analysis of the narrative responses to both free-text questions revealed several themes, including leadership roles and transition of leadership, communication, clarity regarding roles and efficiency at performing those roles (Table 1).

The first theme that emerged was leadership roles and transition of leadership (Table 1). Responses were split with some reporting leadership roles and transitions of leadership did not need to be improved while others reported they did. Illustrative quotations that transition of leadership needed improvement include “there is often times confusion at times of transition”, “everyone left (before plans could be conveyed by the team leaders)”, and “a clear leader was never really established in my eyes”. In contrast, quotations that indicated transitions were appropriate included “[surgical] attending arrived and took over role of primary patient care director”; “leadership stayed with the PEM [Pediatric Emergency Medicine attending] with surgery team assisting, their roles seemed clear”; “leadership was clear, communicative, and collaborative”, and “easy transition and communication between non-organic ED [Emergency Department] entities”.

The second theme that emerged in the narrative responses was communication. Again, some reported communication needed improvement and others reported it did not (Table 1). Illustrative quotations that communication needed improvement include: “often not consistent communication between the ED and TACS [Trauma and Acute Care Surgery]”, “communication of what exams [were needed] was not completed prior to coming to CT [computed tomography]”, “trauma activation text has no information”, “ignored what we said”, and “no clear or closed [loop] communication”. Some examples of responses indicating appropriate communication were, “clear communication about who is holding C-spine”, “easy transition and communication between non-organic ED entities”, “communication with the surgery team was clear”; and “communication was clear, concise, closed-loop, and also anticipatory”.

The last theme that emerged was clarity regarding teamwork and team roles (Table 1). This theme was the least represented in the narrative responses, but a dominant subtheme emerged – that teamwork, delineation of roles, and efficiency of completing roles could be improved. Illustrative quotations include: “no cohesion” and “everyone had their roles but the speed at performing them was rather slow”. Only one response indicated “strong teamwork and good collaboration between the provider teams and providers and staff”.

The narrative responses also highlighted specific knowledge gaps that arose in the trauma resuscitation. For example, one narrative response highlighted that the Belmont (a rapid blood transfuser) was primed incorrectly and stated that this is a recurrent challenge. Another indicated that CyanoKit® (hydroxocobalamin) was not well understood and was primed incorrectly. A third response indicated inappropriate discussion about activating massive transfusion protocol (MTP) prior to a hemodynamically stable patient’s arrival.

Discussion

Results of this single-institution, trauma needs assessment survey revealed that trauma team members think that transitions of leadership and team communication could be improved, and that roles could be more clearly defined and carried out more efficiently. The survey responses and narrative responses were both effective at revealing components of direct patient care that could be improved including keeping the patient warm, priming the Belmont (rapid blood transfuser), and administering CyanoKit (hydroxocobalamin). The results of this pediatric trauma needs assessment survey can be used to guide continuing education in the trauma department at the study institution through implementation of simulations targeted at these areas of need. This work adds to the limited research in the field of developing pediatric trauma simulation programs, and highlights that needs assessment surveys can reveal specific, targetable areas for continuing education. This survey and methodology can also be emulated by other institutions to highlight their unique educational needs.

Needs assessment surveys are critical to education programs to ensure that they continue to meet their educational goals and have the desired impact.15 Implementing a standardized survey, such as the one utilized for this study, will allow educational needs to be evaluated over time. Furthermore, prior research has demonstrated that curricula developed with a needs assessment survey have improved learning and transfer of learning to the participant’s job.16 Despite these known strengths of needs assessment surveys and success utilizing them in adult trauma simulation program development,17 little research has focused on using them in pediatric trauma education and simulation. The areas identified by the needs assessment survey as needing improvement are areas that are known to be successfully targeted by simulations. Specifically, prior simulation programs have demonstrated improvement in teamwork6,18,19 and overall team performance.6,18 Simulations have also been demonstrated to improve specific components of the trauma resuscitation including decreased time to interventions.8 This supports the feasibility of translating the results of the needs assessment survey into a simulation curriculum that will improve trauma team performance.

One of the primary limitations of this study is the small sample size. However, the providers that comprise the typical trauma team at the study institution were represented. Further, thematic analysis revealed common themes that are meaningful to improving the trauma program at the study institution. The responses to this survey are unique to the members of the study institution’s trauma team, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. However, the methodology reported here can be replicated by other institutions to improve their pediatric trauma education. Participants were not required to report their age, race/ethnicity, or sex, so the respondents could be biased towards one age group, race/ethnicity, or sex, which could limit the generalizability of our findings. These components were left off the survey to allow for maximum anonymity for the respondents.

Conclusions

The needs assessment provides a dynamic method of assessing the specific evolving needs of the pediatric trauma team. Areas of improvement identified by the survey can be targeted by simulations to improve the care of pediatric trauma patients. This methodology has general applicability in that it can be used to guide the development of pediatric trauma continuing education curricula at other institutions.

_team-work_domain_questions_with_responses_of_survey_participants._1___completely_disag.jpeg)

_team-work_domain_questions_with_responses_of_survey_participants._1___completely_disag.jpeg)