Introduction

Simulator-based training is on the rise in the evolving fields of interventional radiology (IR) and vascular surgery, shifting away from the traditional apprentice-apprenticeship model.1 Its unique utility provides a structured, learner-centered environment for the acquisition or practice of skills while avoiding harm to patients. As hands-on simulation training advances in residency and fellowship training, so does its utility in medical student curricula.2

The issue of advancing medical student curriculum continues to challenge educators as time constraints and financial limitations compete with the growing demand for physician mentors.3 Additionally, an interventional radiologist shortage exists with a growing need to produce interventional radiologists, particularly within the rural setting.4,5 One solution to meet this growing demand is the introduction of simulator-based training to early medical education. Recent studies have shown that access to hands-on endovascular procedural simulation in preclinical curriculum improves attitudes towards endovascular specialties and increases the likelihood of choosing the specialty in both interventional radiology (IR) and vascular surgery.6,7 Simulator-based training has also been shown to improve students’ knowledge of instruments and techniques utilized by interventional radiologists, such as the Seldinger technique, as well as 3D vascular anatomy and interpretation of angiographic projections.8,9

There has been limited evidence on the utility of 3D virtual reality (VR) models vs. traditional 2D models in the understanding of 3D neurovascular anatomy, with conflicting evidence leaving it unclear whether hands-on training truly impacts knowledge retention.10,11 The Mentice Vascular Intervention System Trainer (VIST) endovascular simulator, a high-fidelity virtual reality simulator, has proven beneficial in enhancing technical skills and interests in vascular surgery among preclinical medical students.7,12 The mechanical thrombectomy simulation in particular has been validated for the use of procedural training in ischemic stroke amongst interventional neuroradiologists.13

Our proposed study aims to assess the use of the Mentice VIST endovascular simulator for teaching 3D neurovascular anatomy to medical students through a simulated mechanical thrombectomy procedure. We aim to evaluate if this hands-on training enhances students’ understanding of neurovascular anatomy, using performance on neurovascular anatomy quizzes based on real patient CT angiograms as a measure, compared to traditional didactic lecture. We also aim to determine if one session of simulation-based training, compared to didactic lecture, can significantly impact medical students’ interest in endovascular specialties.

Methodology

Subject recruitment

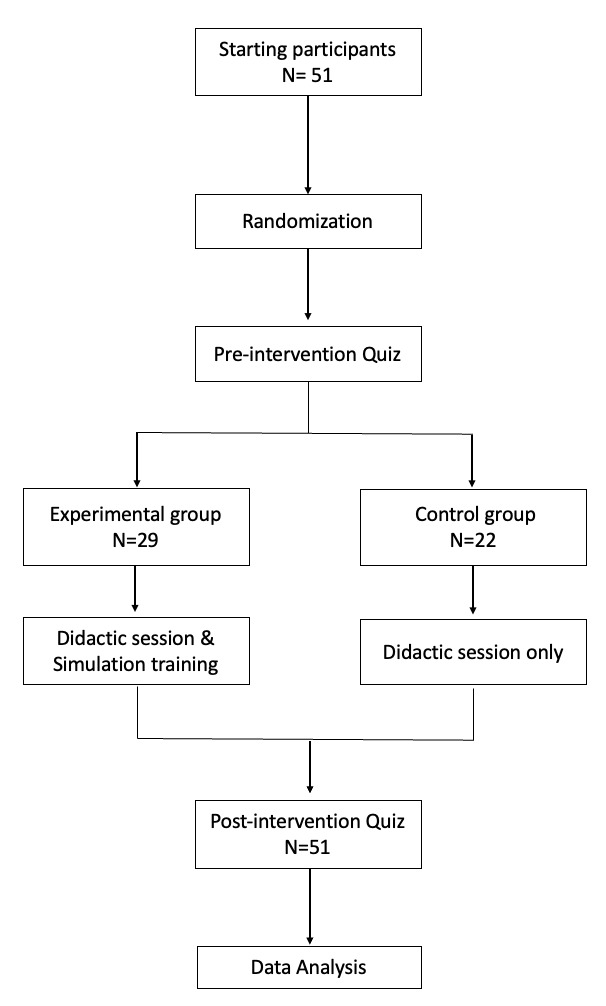

The study protocol was approved by the University of Arizona institutional review board. All students provided written informed consent prior to participation and created a unique identification number composed of combinations of letters and numbers corresponding to their name and birthdate. Medical students from a single university were recruited from the first and second-year classes and prospectively randomized into two groups; a control didactic group and experimental didactic plus simulation group. Participants were stratified according to training year and then randomized into experimental or control groups. Blinding was not performed and convenience sampling was used.

Both groups were administered a pre-intervention survey assessing demographic information and specialty interest (see Supplement A). They were also administered a self-paced neurovascular anatomy quiz, detailed under Neurovascular anatomy quiz.

Both the control and experimental group were then provided with the didactic lecture. The control group was then offered a post-test survey and neurovascular anatomy quiz. Then, they were provided the same hands-on training and simulation session for student educational purposes.

The experimental group received hands-on training from a medical student researcher on the simulator. Students in the experimental group then had the opportunity to run through the simulation themselves with the guidance of the researcher. The students were then provided a post-test survey and neurovascular anatomy quiz.

Didactic Lecture

All participants viewed a previously recorded lecture delivered virtually by a resident Interventional Radiologist following completion of the pre-test quiz. Lecture material includes an introduction to the field of Interventional radiology, therapeutic approaches for ischemic stroke, introduction to mechanical thrombectomy, and a neurovascular anatomy review using anatomical figures and screenshots from DSA studies. Subjects were instructed not to take notes.

Neurovascular anatomy quiz

Computerized tomography (CT) angiograms of real patients without pathology were screenshotted, labeled, and displayed on Qualtrics quiz software for students to identify the vascular structures. Images included different views of the same structure to test spatial awareness. Students were scored on the percentage of correct answers total. Additional images included screenshots from DSA studies. Overall, one question utilized a digital subtraction angiography (DSA) study showing a middle cerebral artery (MCA) occlusion, 12 utilized CT angiography images, and three tested on vascular anatomy concepts without associated images.

Specialty interest survey

Mean level of factors that may deter or motivate students for a career in IR were scored (strongly deters -3, moderately deters -2, slightly deters -1, no impact 0, slightly motivates 1, moderately motivates 2, and significantly motivates 3) for presentation.

Simulation

The Mentice VIST ® (Gothenburg, Sweden) utilizes a physics-based high-fidelity endovascular VR simulator to train clinicians in endovascular techniques. Real endovascular devices, such as guidewires and catheters, are inserted into the high-power computer based system which determines the movement of the devices in real time. The user’s movements are detected by the highly sensitive system and determined in relation to vasculature from 3D vascular representations. The device features a dual foot pedal for fluoroscopy and cineangiography which is done via simulated contrast injection via a syringe. It also features a joystick and buttons that allow rotation of the C-arm and patient table. The simulation provides patient vital signs such as blood pressure and pulse with real time feedback.

The mechanical thrombectomy simulation guides users in a step-by-step manner to identify a right M1 (the initial portion of the MCA, originating from the internal carotid artery bifurcation) occlusion, select the appropriate vessel, and relieve the obstruction using a stentriever. This simulation has been validated to augment the training experience for ischemic stroke intervention.14

Data Collection

Each subject created a unique participant code that was used to link their pre- and post-quizzes for analysis. The effect of hands-on virtual reality training was assessed by changes in pre- and post-test scores (delta scores). Other factors, such as attitudes towards IR and surgery as a career were collected pre- and post-intervention to analyze the effects of hands-on training on specialty interest within IR and general surgery/surgical subspecialties specialties.

Statistical Approach

SAS 9.4 was utilized for all statistical analysis and chart creation. Differences by treatment group and by sex were examined using chi square distribution analysis. The student’s t-test was used to examine differences in continuous variables such as age. Responses for the agreement scales were assigned numbers (1 to 5 for strongly disagree to strongly agree) and mean scores summarized by group. However, as the agreement and motivational scales were treated as categorical data, chi square distribution tests were used to examine potential differences.

To evaluate the distribution of change in neurovascular anatomy quiz scores (post-test minus pre-test) between the Control and Experimental groups, we generated comparative histograms overlaid with both normal distribution curves and kernel density estimates (KDE). Each group’s change scores were plotted as frequency histograms, with percentages represented on the y-axis and score changes on the x-axis. Overlaid curves included a normal distribution curve, computed using the group-specific mean and standard deviation, and a kernel density estimate, representing a non-parametric smoothed estimate of the probability distribution. Box-and-whisker plots were included beneath the histograms to summarize the central tendency, variability, and 95% confidence intervals of change scores for each group.

Results

Study Participants

A total of 51 students were enrolled in a convenience sample, of which 29 were randomized to the experimental group and 22 to the control group. The sample comprised 72.7% MS1 (first-year medical students), 7.8% MS2 (second-year medical students), and 19.8% MS3 (third-year medical students) detailed in Table 1. Participants were 49% female, with a mean age of 25 + 2.9. Most participants (82.4%) had neither parent as physicians. 17.7% listed diagnostic radiology (DR) in their top 3 specialties of interest, 33.3% listed IR, and 54.9% listed general surgery. There were no significant baseline differences in demographic variables or specialty interest between the two groups.

Most participants (78.4%) had no prior experience with medical procedure simulation. 94.1% had no prior experience in endovascular procedure simulation specifically and 88.2% had never observed an endovascular simulation on a real patient, as described in Table 2. There were no significant differences in levels of exposure between the two groups.

Specialty interest

Eight (36.4%) of the Control group selected IR as one of their top three areas of interest, and this ranking did not change post-test for the control group. In contrast, nine (31.0%) students from the experimental group initially selected IR as one of their top 3 areas of interest, and an additional four (13.8%) included IR post-intervention that did not previously list IR in their top 3 specialties of interest Thus, IR interest increased by 13.8% in the experimental group and did not increase in the control group, although this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.579) (figure).

Ten (45.5%) of the Control group selected Surgery (including surgical subspecialty) as one of their top three areas of interest pre-intervention. Following didactic lecture, two students dropped surgery and two added surgery from their top three specialties of interest. In contrast, 17 (58.6%) students in the Experimental group initially selected surgery as one of their top three areas of interest and 19 (65%) selected surgery post-intervention. Thus, surgery and surgical subspecialty interest increased by 6.9% in the experimental group and did not increase in the control group, although this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.169) (figure 3).

Delta score in quizzes: total, control, simulator

Although both groups demonstrated mean score increase, there was no statistically significant difference between the control and experimental groups in mean score changes post-intervention (2.36 + 2.3 vs 2.10 + 2.4, p = 0.709). The Experimental group shows a broader distribution, and a higher frequency of positive change compared to the Control group when plotted on histogram, although this was not found to be significant (figure 4).

Follow-up Survey

A follow-up survey was sent via email to all 51 students who participated. The control group had the same hands-on learning simulation session as the experimental group following the completion of their post-test quiz to ensure equal educational opportunities for all students. Survey questions are included in Supplement B. A total of 31 students participated. In the follow-up period of one year, one student rotated with IR, three students rotated with DR, and three students rotated with vascular surgery. Of these ten students, three responded “definitely yes” and three responded “probably yes” to the question: “Did your participation in this simulation enhance your experience on the(se) rotation(s)?”. For reasons why, 4 cited “better anatomical knowledge,” 3 cited “more knowledge about vascular diseases and interventions,” and 1 cited “more comfort with IR procedures.”

Discussion

This randomized controlled trial examined whether adding a high-fidelity mechanical thrombectomy simulation to a didactic lecture, compared to didactic lecture alone, improved medical students’ understanding of 3D neurovascular anatomy and influenced specialty interest. Both control and simulation groups demonstrated measurable improvement in anatomy quiz scores (mean increases of 2.36 and 2.10 points, respectively), indicating that structured instruction, whether lecture-based or hands-on, can enhance early anatomical knowledge. While our randomized controlled trial did not demonstrate statistically significant improvements in neurovascular anatomy quiz scores or specialty interest following simulation-based training, we believe that simulation remains a valuable tool in preclinical medical education.

The lack of a significant difference in neuroanatomy performance between groups may be attributed to the short, single-session nature of the intervention, rather than an absence of simulation benefit. Notably, the broader distribution of improved scores within the simulation group suggests greater individual variability in response to hands-on learning, warranting further investigation with repeated or prolonged exposure. Similar findings have been reported in the literature. A meta-analysis by Zhao et al. demonstrated that VR-based anatomy education led to modest but significant gains in test performance compared to traditional instruction across 15 randomized controlled trials (SMD = 0.58).15

Additionally, simulation participants reported a 13.8% increase in interest in IR and a 6.9% increase in interest in surgical specialties, while no change occurred in the control group. Although these changes did not reach statistical significance, they reflect a trend toward simulation fostering curiosity in procedural careers, consistent with prior literature. Stoehr et al. (2020) similarly investigated the effect of a single 90-minute IR course featuring endovascular simulation among 305 fourth-year medical students in Germany.6 They found that students rated the simulation as highly effective and showed a statistically significant increase in interest in pursuing IR. Additionally, Lee et al. (2009) conducted an 8-week vascular surgery elective among preclinical students involving weekly 90-minute mentored simulation sessions.7 They reported significant improvement in technical performance and a sustained increase in interest in vascular surgery and IR at one-year follow-up, suggesting that more longitudinal simulation exposure can shape early specialty preferences. While our study employed a more condensed intervention, the numerical trends toward increased specialty interest in our simulation group reflect similar patterns.

In our one-year follow-up survey, students who engaged in the simulation cited lasting benefits, including enhanced anatomical understanding, greater procedural familiarity, and increased comfort with wire and catheter manipulation. 79% self-reported improved 3D anatomical comprehension (Likert 4 or 5), and 58% noted increased procedural confidence, suggesting that simulation may foster more sustainable educational outcomes than quiz scores alone can capture. Similar results have been seen in a randomized trial by Du et al., where medical students exposed to collaborative VR learning showed significantly improved anatomical knowledge retention compared to traditional methods.16

Beyond content knowledge, immersive tools have consistently been associated with increased learner satisfaction and engagement. A study by Ekstrand et al. comparing immersive VR to textbook-based neuroanatomy instruction showed equivalent quiz performance but higher spatial understanding in the VR group as well as confidence in their understanding of neuroanatomy.17 This is especially relevant in anatomical education where learners must mentally reconstruct 3D anatomical relationships from 2D sources.

There are several limitations to our findings, including a modest sample size, potential pre-existing interest in procedural fields among participants, and a single-site study design that may affect generalizability. Additionally, the use of identical pre- and post-tests may have introduced recall bias, and the short-term follow-up limits insights into long-term retention or career decision-making. Finally, self-reporting, such as in the follow-up survey, does not provide an objective measure but can provide further insight into the subjective experience of students and their perceptions towards this simulation experience.

Ultimately, this study contributes to a growing body of literature advocating for early, immersive exposure to procedural medicine. While our results did not demonstrate a statistical advantage of simulation over didactic methods in improving anatomy quiz scores, the consistent trends in specialty interest, subjective learning gains, and alignment with prior studies support its continued integration into medical curricula. Further large-scale, longitudinal research is needed to more precisely quantify simulation’s role in shaping competency and career trajectories in interventional and surgical specialties.

Conclusion

Although our study did not demonstrate statistically significant improvements in neurovascular anatomy quiz performance or specialty interest following simulation-based training, the broader educational value of simulation remains clear. The trends observed, supported by learner feedback and prior research, suggest that even brief exposure to high-fidelity simulation can enhance spatial understanding, motivate learners, and spark interest in underrepresented procedural specialties. These subjective gains, combined with the growing evidence base on simulation’s cognitive and motivational benefits, underscore its potential as a powerful adjunct to traditional didactic education. Future studies should focus on longer-term and repeated interventions, broader curricular integration, and larger, multisite trials to more fully capture the transformative potential of simulation in medical education.