Background

Choledocholithiasis occurs in ~8-20% of patients undergoing cholecystectomy.1 Bile duct stones bestow an increased risk of cholangitis and biliary pancreatitis. The two most common treatment options are cholecystectomy with common bile duct exploration (CBDE) as a single-stage approach or a cholecystectomy followed by an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) through a two-staged approach.

ERCP stone clearance rates are ~93-96%. However, this comes at a cost of an additional procedure, anaesthetic, and up to 15% morbidity (pancreatitis, perforation, haemorrhage, cardiopulmonary complications) and a mortality of up to 1%. In the management of cholecystocholedocholithiasis, ERCP was also found to be less cost effective than single-stage laparoscopic transcystic management.2 Importantly, long-term studies on ERCP have also recently been published which have shown a benign complication rate of 16.3% (over 131months). These complications included recurrent stones, cholangitis and pancreatitis. Additionally, they found a malignancy rate of 1.4% which included pancreatic cancer, cholangiocarcinoma, intrahepatic neoplasms and ampullary cancer.3

In 1998 in America 40% of patients with choledocholithiasis underwent a surgical bile duct exploration but by 2013 this had plummeted to 9%. Laparoscopic TCBDE became a procedure for those with advanced laparoscopic skills, but recently a revitalisation of the technique has been advocated for all general surgeons. The comeback of the TCBDE has been made possible by the increased laparoscopic and robotic skills of trainee surgeons, the increased availability of training models and the increased armamentarium of tools for extraction of stones.4,5 Additionally, access to ERCP hasn’t significantly increased as it is still a procedure only available at select, typically metropolitan facilities.

In the hands of a general surgeon single-stage CBDE is a safe and effective operation with equal to or greater success than ERCP and should be considered first line.6,7 A recent study from Australia suggests that CBDE should not be limited to a specialised hepatopancreatobiliary (HPB) surgeon but is safe with comparable success rates in the hands of a general surgeon.8 Hence this is an operation in which all general surgery trainees should be trained and proficient in by the end of their training.

The clearance rate of TCBDE is 80-100%. Benefit has been shown from preserving the Sphincter of Oddi to prevent biliary reflux and bacterial contamination of the biliary tree which can lead to primary choledocholithiasis recurrence.9,10 Additional benefits include a decreased length of hospital stay, decreased healthcare costs, with similar morbidity and mortality rates.6,11,12 It also provides an avenue for patients with altered foregut anatomy (e.g. roux-en-y reconstruction) to have a simple treatment compared to a laparoscopic-assisted or double-balloon enteroscopy. Importantly, long-term studies on ERCP have also recently been published which have shown a benign complication rate of 16.3% (over 131months). These complications included recurrent stones, cholangitis and pancreatitis. Additionally, they found a malignancy rate of 1.4% which included pancreatic cancer, cholangiocarcinoma, intrahepatic neoplasms and ampullary cancer.3

The current barriers to TCBDE are the logistical operating theatre scheduling, inadequate reimbursement and additional skills requirement, which is secondary to the inadequacy of the current training environment.13 The inadequacy of training in this technique has also been acknowledged in America and research currently being conducted on how best to train American residents given limited clinical exposure. What we must ask ourselves is whether in Australia, as the next generation of surgeons develop, will they be able to take on this task of reclaiming the bile duct? Will they be skilled and educated to perform TCBDE?

This study aims to assess if the trainees themselves feel adequately trained for this procedure and/or when this confidence in competency occurs. This study focusses on the readiness of the current general surgery trainees and the most recently qualified general surgeons of Australia and New Zealand.

Methods

Ethics approval was applied for and granted by the Northern Health research development and governance unit (RDGU) on 3/4/2024. On 16/04/2024 an invitation email was sent via General Surgeons Australia (GSA) to the current Australian and New Zealand trainees and recently appointed fellows (qualified within the past 3yrs (2020-2023)), 725 eligible participants. This email included an invitation and information on the study with a link to the online survey for completion. (See appendix A). By accessing the study link, participants provided implied consent to participate in the study. A reminder email was sent on 14/5/2024 and the survey closed on 31/5/24. Data was collected online using SurveyMonkey, which is a reputable secure online survey creation platform. All surveys were completed anonymously, without any identifying factors.

Responses were recorded and assessed using statistical and thematic analysis. Categorical variables were compared by Fisher’s exact test and presented as frequencies with percentages. All statistical tests were 2-sided with an alpha of 0.05. Qualitative responses were categorized to determine themes and patterns amongst the data. Given the lack of prior studies in this area, all analyses will be performed in an exploratory fashion. Missing data was excluded from the analysis.

Results

A response rate of 14% was achieved (102/725). Table one demonstrates the distribution of the participants according to their training level.

They participants were predominantly recently accredited fellows with 52% (53/101) being in their first to third year post training. 33% (33/101) were from the new GSET program. The majority had completed 2-3yrs of unaccredited training prior to being accepted on the program (72%). The participants were distributed in a geographic manner according to the training positions available across Australia. 63% (64/101) had worked in a HPB unit prior to completing the surgery.

As demonstrated in table two, there was considerable variability in the number of laparoscopic cholecystectomies that the participants had been involved with a peak at 251-300 (~16%). In 51-75% of the cases the participants were primary operator in these cases.

There was less variability in the number of bile duct explorations the participants had been involved with, as demonstrated in table three.

The majority (71.5%) had participated in <20 and on average were the primary operator in 27% of the cases. 5 participants reported being involved with >50 bile duct explorations (4/5 of these were 3rd year fellows). The techniques employed by those completing bile duct exploration were evenly distributed with 34% (29/101) using choledochoscopy, 33% performing fluoroscopically guided explorations and 33% using both techniques. 60% of participants had not placed a stent trans-cystically.

The participants reported varied levels of comfort in performing bile duct explorations but average comfort level on a scale of 0-10 was 4.5. Figure one demonstrates the number of additional cases participants reported that they would require to be comfortable with performing TCBDE.

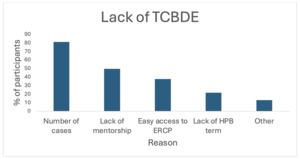

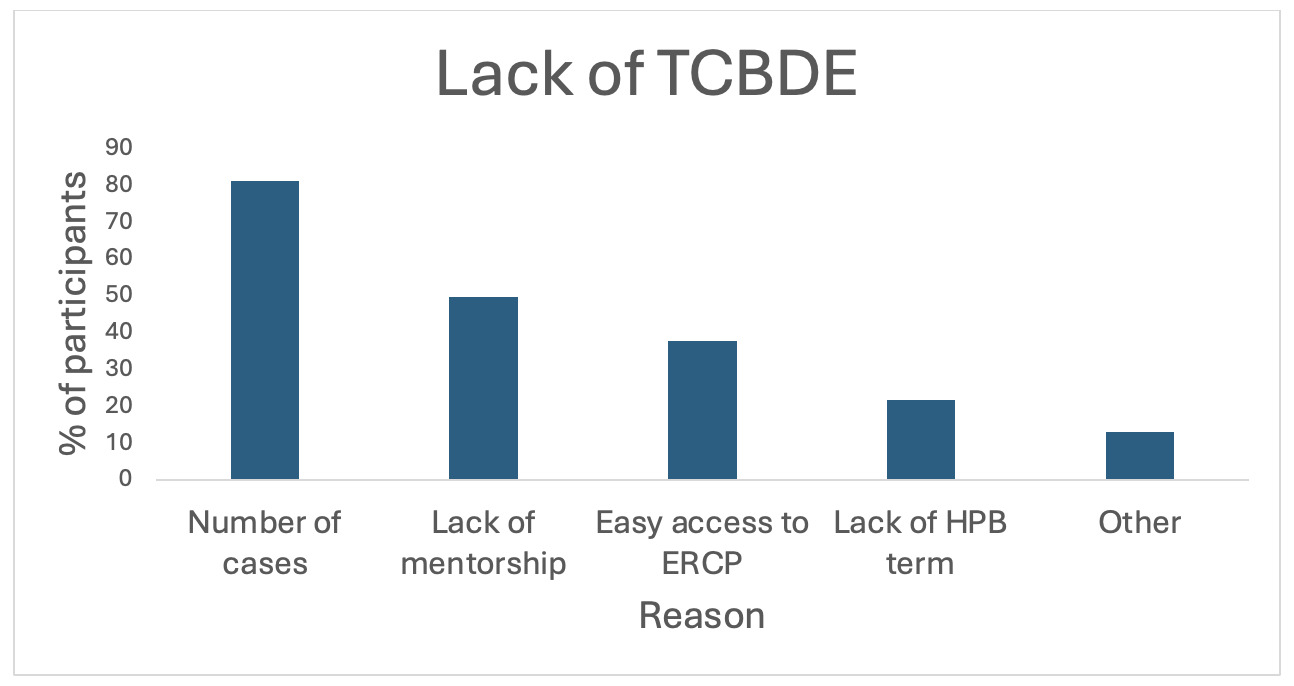

Only 10% of participants had completed a simulation workshop for TBCDE. 9/10 of those who participated found the workshop helpful in increasing their confidence in TCBDE. This was reflective in their confidence score as their average was 6.6 which was statistically significantly higher (p=0.03) than the participants who did not participate in the workshop. The participant that didn’t find it helpful explained that was because there was significant time lapse between the workshop and their clinical experience. Figure two demonstrates the main barriers selected by the participants. It should be noted that, 86% of the participants who selected ‘lack of a HPB term’ had not undertaken a HPB term.

The free text question regarding improvement to training allowed for the selection of ‘other’ to be explored. 40 participants provided further recommendations for improving training and the barriers that they experience. The main theme from these comments was that the biggest barrier was lack of supervisor experience and enthusiasm in the in the technique which meant that the participants were not being trained.

Additional barriers identified were access to cases, access to equipment, skills of theatre staff and the perception that it is a subspecialised surgical skill of an HPB surgeon. The participants did express their enthusiasm to learn, and that further training and workshops would be well received. Two participants commented that at a minimum, training in trans-cystic stent insertion is a required skill to safely manage patients with choledocholithiasis. Additional recommendations were to educate the unaccredited registrars about the procedure and its indications and to make it a core skill during training.

Discussion

The discrepancy between the number of cholecystectomies that trainees have been involved in and the actual number of TCBDE performed suggests a gap in exposure to this procedure. This disparity could be attributed to both the incidence of choledocholithiasis, which affects approximately 12% of patients undergoing cholecystectomy and the preference for ERCP over surgical bile duct exploration.14

Analysis of Trainee Exposure

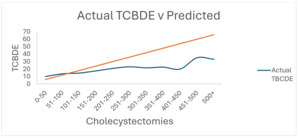

When comparing the actual number of TCBDEs that trainees were exposed to against the predicted number based on incidence of choledocholithiasis, there is a statistically significant difference (p=0.0306), represented graphically in figure three.

The data shows that only 25% of trainees and recent fellows have been involved in the expected number or more TCBDEs, highlighting a significant training deficiency. This trend has been shown to have filtered down to graduating American residents performing fewer cases and having a lower confidence over their operative abilities.15 Additional studies have demonstrated the limited trainee exposure to CBDE (on average one CBDE) as well as other operations and has brought about concerns for declining operative autonomy in trainees.16,17

This sentiment has been echoed by Dr Eric Hungness at the 2016 Surgical Spring week organised by SAGES (Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons). His team at the Northwestern hospital in Chicago created a CBDE mastery requirement for all their surgical residents which involved a pre-curriculum test, curriculum and post-curriculum (with additional remedial practice if required) to address the inadequacies of training. His results are encouraging with increased number of CBDE with less complications and readmissions.

As the next generation of surgeons develop, will they be able to take on the mantra of reclaiming the bile duct? Will they be skilled and educated to perform TCBDE? It is difficult to assess the learning process and proficiency at a task, as they are complex and multifactorial concepts. A contemporary study aimed to summarise the current literature on the topic but concluded with a recommendation for further analysis due to the heterogeneity amongst the studies.18 The use of complications, conversion to open operations, length of stay and operating time are not sensitive nor specific in the assessment of proficiency at TCBDE.

Comfort Level and Training Opportunities

Despite limited exposure, participants estimated that they would feel comfortable performing TCBDE after approximately 39 cases (range 34-48), highlighting that proficiency is attainable with adequate hands-on experience. This limited exposure may result from supervisors’ personal inexperience with TCBDE, a strong reliance on ERCP, or logistical challenges such as limited operating theatre availability and equipment access. Addressing these barriers is essential to fostering a cultural shift within the surgical community toward more widespread use of TCBDE.

A recent systematic review by Sivakumar et al. found that 32.5 cases are required to achieve proficiency in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs, a procedure with technical demands that are distinct from TCBDE.19 Despite the procedural differences, it is noteworthy that the number of cases required for proficiency in both contexts is quite similar. In the meta-analysis, proficiency was assessed by analysing changes in operating time through cumulative sum (CUSUM) control charts, stationarity tests (KPSS), and the plateauing of the operating time curve, either observed directly in consecutive cases or inferred from moving averages of multiple cases.

While achieving a specific case number can provide valuable experience, many studies suggest that numerical targets alone do not guarantee surgical proficiency, as individual learning curves vary. This recognition has driven a paradigm shift in surgical training, emphasizing the assessment of proficiency rather than solely meeting case number targets.

Repetition, however, remains crucial to building confidence. Even when a surgeon possesses the necessary skills and technical competence, confidence often requires performing a procedure several times. This is especially relevant for trainee surgeons and recently graduated fellows, who may need substantial repetition to feel secure in their abilities and ready to independently perform certain procedures, which is what was assessed in this study.

Educational Resources and Simulation Models

Educational resources, such as the “Behind the Knife” podcast series and simulation models (using porcine aorta segments or commercially available training kits), provide valuable training opportunities.20 The TCBDE Surgeons Australia (GSA) workshop is a notable initiative, offering a half-day session to introduce trainees to laparoscopic CBD exploration. Feedback from participants indicated that most found the session useful, although one participant felt the course did not fully benefit them due to the time elapsed since their last experience with TCBDE. This highlights the need for more regular access to such courses to reinforce skills and build confidence over time.

The structure of this course mirrors the approach taken when laparoscopic cholecystectomy was first introduced in Australia. At that time, the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons played a pivotal role in assessing, disseminating, and standardizing the procedure nationwide. Through workshops and a national audit, the College defined criteria for laparoscopic cholecystectomy, ensuring safe community uptake while maintaining quality standards.21 A similar approach, led by a governing body, may be beneficial to regulate and encourage the adoption of laparoscopic CBDE.

Cultural Shift and Competency Requirements

The study highlighted that, although 63% of participants had completed an HPB term, only 22% felt it significantly contributed to their CBDE competency. Interestingly, 86% of those who hadn’t completed an HPB term believed it would be beneficial for developing this skill. This discrepancy reflects a broader perception that TCBDE is a specialized procedure, potentially contributing to its underutilization among general surgeons.

The Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) has outlined guidelines for surgeons performing CBDE, emphasizing that it is not exclusively an HPB specialty skill. The requirements include:

-

A thorough knowledge of biliary anatomy.

-

Proficiency in performing and interpreting intraoperative cholangiograms or laparoscopic ultrasounds.

-

An understanding of various approaches to the common bile duct and the ability to choose the most appropriate technique for each situation.

-

Competency in stone extraction methods (flushing, balloon, basket, and choledochoscopy).

-

The ability to perform intracorporeal suturing when a choledochotomy is necessary.

These criteria are achievable for many general surgeons, even those without formal HPB training, especially with targeted upskilling and practice. This inclusive approach suggests that CBDE could be more widely adopted by non-HPB surgeons, broadening the skill set of general surgeons and potentially reducing the dependency on ERCP in certain settings.

A significant step forward would be incorporating TCBDE as a core competency in surgical training programs. Integrating this skill within the foundational training curriculum would ensure that future general surgeons receive adequate exposure and practice, making CBDE a standard part of their operative repertoire. As with the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, which was successfully implemented through structured workshops and skill-building programs, similar strategies could normalize TCBDE and help instigate a cultural shift within the surgical community.

By fostering a broader understanding and appreciation for TCBDE within general surgery, we can help overcome the current barriers associated with its adoption. The inclusion of TCBDE in routine practice may also increase comfort levels and confidence among general surgeons, ultimately leading to improved patient care and greater autonomy in managing choledocholithiasis cases.

Future Directions

An additional research avenue could involve reassessing trainee confidence levels after introducing a minimum TCBDE training requirement, either through live surgical cases or simulation-based education. A comparative analysis of these training modalities would offer insights into the most effective methods for developing proficiency in TCBDE, helping to establish evidence-based goals for general surgery trainees.

Conclusion

Trainees’ limited exposure to TCBDE is largely driven by the preferences of their mentors, likely due to the mentors’ own limited training or reliance on ERCP. Addressing this issue requires resolving equipment availability challenges and offering re-education opportunities for senior surgeons. By encouraging a cultural shift towards more frequent utilization of TCBDE, workshops targeting practicing senior surgeons may help bridge the gap in training, ultimately benefiting the next generation of general surgeons. Instituting competency-based requirements for TCBDE within surgical training programs will ensure that future surgeons possess the skills necessary to perform this procedure, integrating it as a core competency in general surgery.