Introduction

Cadaver dissection (CD) has been a cornerstone of anatomy education for centuries, offering students invaluable hands-on learning experiences. While CD has traditionally emphasized anatomical understanding, there is a need to modernize these practices to align with contemporary medical training. Limited exposure to procedural skills during undergraduate studies hamper students’ ability to appreciate the application of anatomy in modern medicine and contributes to their inadequate preparedness for residency. While research has explored the effectiveness of lightly embalmed cadavers in acquiring procedural skills, a conspicuous gap exists in comprehensive reviews assessing the impact of exposing undergraduate medical students to procedural skills using fresh frozen cadavers. This review endeavors to fill this void, empowering educators to better prepare the next generation of physicians for the rigors of modern medical practice and facilitating their seamless transition into internship and subsequent professional stages. Cadavers are typically dissected by system while an instructor simultaneously teaches using the anatomical structures. In recent years, medical school curriculums have expanded upon this and have utilized advancement in technology to provide anatomy tables that serve as a virtual dissection of a cadaver and other such options. While this offers a more cost effective and accessible option to anatomical training, many medical schools still prefer to expand on the hands-on experience that a cadaver provides.

Programs have been piloted in research studies to allow not only the use of cadavers for teaching, but also for surgical skills training. Surgical skills training requires the use of lightly embalmed or fresh frozen cadavers as this best simulates the condition of a living person. The use of fresh frozen cadavers has been proven effective in many studies at the residency level for specialty surgical training.1 It has also been studied and proven to be an effective model for simulating Ultrasound imaging on a living patient.2 Surgical skills and most procedures are best learned by hands on experience. With limited time spent on a surgical rotation in medical school, different preceptors, and levels of student expertise; students can have minimal exposure to specific procedures.3 Students also must be able to practice surgical skills on models that resemble human skin, depending on the factors listed above, that practice can be less than required to excel in a surgical residency.4

The literature shows that there is benefit in implementing the use of cadavers, specifically lightly embalmed cadavers in the instruction of procedural skills. Lightly embalmed cadavers have also been used to further student’s basic science knowledge by allowing students the opportunity to re-learn material in a hands-on approach. Biopsies of cadaver tissue were taken and prepared as microscopic slides so that students could identify the tissue and have exposure to histology topics that they had already covered. This proved beneficial in overall retention of basic science knowledge.5 While this topic has been studied, implementation of the use of fresh frozen cadavers has not been integrated into curriculums of medical schools. There have been a handful of studies done on the implications that such integration would have on student skill level and confidence. However, there has not been a comprehensive review of the published literature. The reviewed articles provide data to address a hypothesized solution to a larger concern; the surgical/procedural skill level needed for a seamless transition to intern year of residency.

Methods

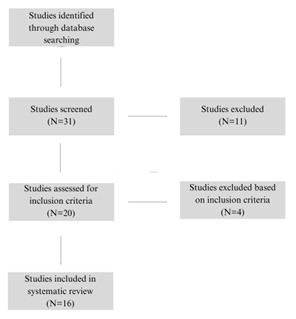

PubMed, JAMA, and Google Scholar were independently searched, using specific search terms. Terms such as “cadaver use in medical education”, “fresh frozen cadaver”, “procedural education cadavers”, and “cadaver surgical training” were used in the search engine and relevant articles were selected based on the results. A date for exclusion of studies was not set. These criteria were set so that a maximum of studies was able to be reviewed. Each article was screened to ensure that it met inclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria was defined as lightly embalmed/fresh frozen cadavers used for teaching surgical or procedural skills to medical students. Exclusion criteria included studies that were not performed on lightly embalmed/fresh frozen cadavers, studies that were performed at the residency level, and the use of fresh frozen cadavers for things other than procedure-based learning and training. Figure 1 depicts the process in which the studies were chosen for review.

As the figure shows, there were initially 31 studies screened with 11 excluded based on initial abstract and title. 20 studies were read and evaluated on inclusion/exclusion criteria. 4 were omitted as they were conducted at residency programs, not medical schools. 16 studies were included for review.

In each study the following measures were defined: number of participants, pre-survey completion, post-survey completion, prior surgical/procedural experience, p-value of student confidence increase, p-value of performance increase, p-value of student knowledge, specialty training focused on by the study, and the number of skills taught. The skills taught were then listed for each study. This allowed for better comparison of the results of each study and overall understanding of what each study tested in their implemented program training using the fresh frozen cadavers.

Results

The studies that were reviewed evaluated a variety of surgical/procedural skills. These skills were all taught and performed on fresh frozen cadavers in medical school training. Most of the procedures were taught to groups of third or fourth year medical students and were more advanced. However, there were a number of studies that taught basic suturing to first and second year medical students. Some studies focused on teaching only a couple of procedures while one study taught 27 procedures. Most of these studies utilized the fresh frozen cadaver in a pilot program that was implemented to teach medical students basic technical skills on the specimen that most resembled a living human. The specific procedures taught in each study are listed in Table 1.

Assessment of Skills

The studies reviewed analyzed different variables, however, most of the studies utilized overlapping methods or evaluated similar variables. Many of the studies surveyed participants prior to teaching skills on the fresh frozen cadaver as well as after the pilot program was concluded. Most of the surveys had students rank their confidence and knowledge prior to and after exposure to technical skills on the fresh frozen cadaver. The p-value of these differences was then tabulated within each study. In every study that evaluated knowledge and confidence before and after the use of the fresh frozen cadaver showed a statistically significant increase despite the number of skills taught. Many of the studies evaluated student’s performance. These studies usually had the professor or physician leading the program observe the student perform the newly taught skill on the cadaver and then would rate their performance. If this category was evaluated, there was a consistent statistically significant increase in performance from before to after the skills program. Some of the studies also tallied how many students had prior surgical/procedural experience. Despite the number of students with previous exposure, there was still a significant increase in confidence, performance, and student knowledge across the board. While some studies did not include many participants, the results of these studies showed the same trend in data as studies that had a larger sample size. There were also a large variety of specialties that each study affiliated with, however, many of the skills taught are utilized by multiple surgical specialties.

Results of the Studies

Overall, the trend of the data shows that the use of fresh frozen cadaver in surgical skills training increases students’ confidence, performance, and knowledge regardless of prior surgical experience, number of skills taught, and how long each program lasted. In addition, a few of the studies surveyed students on if they preferred to be taught surgical skills on the fresh frozen cadaver, and all the students surveyed preferred the skills lab on the cadaver. This analysis of the published data shows that the incorporation of fresh frozen cadavers into medical schools’ curricula would be beneficial to students’ learning and their success in preparation for an intern year of residency.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to analyze and characterize the data in the published literature. The data showed that there was a consistent significant increase in student confidence while performing procedures, skill of the student while performing the procedure, and overall medical knowledge. There was also positive feedback from the participants of the included studies that learning surgical skills by use of the fresh frozen cadaver model was superior to other techniques that they had encountered. It is of note that while the procedures taught in each study did have some overlap, there was a large variety of surgical skills taught. Yet, the data for least complex to most complex procedure had the same result of improving the student’s education.

Limitations of Included Studies

Potential limitations of the studies included in the review are that most of the studies were not reproduced. The studies piloted programs that provided supplemental instruction to procedural skills on lightly embalmed/fresh frozen cadavers, but these programs were not then implemented into the curriculum or piloted again. The other limitation to these studies were the varying amounts of skill that the participants had coming in. While this did not affect the overall results of the studies that accounted for this, not all the studies did. Another issue that was found in two of the studies was the small participant pool that the researchers collected data from.

Clinical Implications

This comprehensive review of the literature proves that regardless of the procedural skill taught, the use of lightly embalmed/fresh frozen cadavers in pilot programs at medical schools is beneficial to students. If the use of cadavers for this teaching principle were incorporated into medical school curriculums there would be greater student confidence when entering surgical rotations and procedure heavy residency programs. The use of lightly embalmed/fresh frozen cadavers for surgical skill training would also increase student skill and knowledge. This would undoubtedly lead to a more seamless transition into surgical residencies and allow for better procedural outcomes in medical school and residency.

Accessibility and Challenges of Fresh Frozen Cadavers

Many institutions opt for more cost-effective options of embalming as lightly embalmed/fresh frozen cadavers are more costly. In addition, cadavers that have received other types of embalming will last longer than lightly embalmed specimens. This allows for students to utilize the specimen for the year that they have anatomy lab. However, fresh frozen cadaver can be re-used by students. If the cadaver is used for training of surgical skills, it can then be re-used by students for dissection and suturing practice, allowing for the maximum educational gain of the donor’s gift.6 This could be a beneficial option for schools that do not have as many opportunities for surgical skills training, where the added cost would be well spent for the additional experience.

Implications for Medical Education

The comprehensive review of the literature shows the need for better procedural skill education among medical students. When trial programs have been instituted into medical school curriculums, students have consistently reported that these trial programs should be a pillar of their education. These trials have shown improved knowledge and skill in procedural skills. This is exceptionally useful at schools that do not have access to a strong surgical skills simulation center or access to other modalities of surgical training. While these programs would be an investment for medical schools, the benefit would arguably outweigh the cost as it would better prepare students for residency. It would also serve as a way that residents could further perfect their procedural skills outside of the hospital. Additionally, a medical school that is capable of fresh frozen cadaver dissection holds a significant attraction to students applying to their program as well as prospective faculty.

Recommendations for Future Research

Many of the reviewed studies utilized participants who were third- or fourth-year medical students. Further research of teaching of surgical skills on fresh frozen/lightly embalmed cadavers should also include first- and second-year students or follow students throughout all four years of medical school while being taught procedures using the cadaver model. There should be further research on the constraints of medical schools obtaining lightly embalmed/fresh frozen cadavers and implementing the use of them as a model for procedural skill training into the curriculum. There should also be studies done specific to each institution that would want to implement this model of training to assess what the students at that medical school need additional skill training in.

Conclusions

This review of the literature provides evidence that supports positive outcomes of using lightly embalmed/fresh frozen cadavers in medical student education when teaching procedural skills. Due to the unanimous positive results and increased need for early instruction in surgical skill, it is necessary for further research to be conducted in obtaining lightly embalmed/fresh frozen cadavers at medical institutions. Further research should also be conducted based on individual medical school programs to identify the greatest need for training in procedural skill amongst the students there. Future research should also include students that are in their first and second year of medical school. The conclusions drawn from this comprehensive review show that the use of lightly embalmed/fresh frozen cadavers for surgical/procedural skills training in medical school increases confidence, skill, and knowledge. While the premise of body donation is based on the choice the donor made pre-mortem to serve as an educational tool to advance the field of medicine; it would be in the best interest of that principle and in the best interest of the student’s learning experience to incorporate this model into the curriculum of our medical schools.