Introduction

Gender-affirming care (GAC) includes medical, psychological, and surgical interventions that allow individuals, particularly transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) people, to successfully affirm their gender identity.1 With rising demand for GAC, residency programs are facing the need to provide the necessary care to patients as well as relevant education to their trainees.

Curriculum enhancement and cultural responsiveness training are crucial in reducing healthcare disparity amongst TGD patients.2 Additionally, a vigorous clinical exposure is imperative in transfer and application of knowledge.3 Currently, there are no formal requirements or guidelines for programs to ensure adequate exposure to GAC. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has instilled requirements to have programs train their residents on culturally sensitive medical treatment, such as abortion care, and similar requirements can be established for programs with regards to GAC.4 The approaches used to educate trainees are also not extensively explored. In a systematic review by Jecke, et al., authors discussed that the current modalities on GAC within health professions education include didactic lectures addressing stigmatization of TGD patients, increasing affordability, seminars, as well as simulations, though the total time spent is frequently at 2 hours.5

As uncovered in the second study of this dissertation, What interventions can be utilized to enhance gender-affirming surgery education?,6 one of the initial steps in designing and executing a curriculum on GAC includes teaching on foundational concepts, terminology, and sensitive and effective communication. There are currently various curricula that have been designed and made available for public use, such as Harvard Medical School’s Sexual and Gender Minority Health Training Modules through the Fenway Institute.7 Modules through other institutes on similar topics relating to caring for TGD patients have been released.8,9 These learning materials deliver training content about GAC but do not tend to include evaluation components. In addition to providing content, there is room for development of a comprehensive, efficient, and user-friendly evaluation tool that learners can utilize to test learning. The aim of this project is to develop and gather validity evidence for an assessment tool to measure trainee knowledge on foundational topics that concern care of TGD patients. This tool can be used part of a group of materials that educators may utilize to enhance education on TGD care.

Methods

Objectives

We created a 15-question test using blueprinting.10,11 Bloom’s taxonomy12 was considered when developing the following learning objectives adapted from Harvard Medical School’s sexual and gender minority health care competencies for medical students13:

-

Describe sex, gender, gender identity, gender expression, gender diversity, and gender dysphoria.

-

Define sexual-orientation and identity.

-

Determine strategies to address inequities in gender minority health at individual and interpersonal levels.

-

Develop strategies to mitigate unconscious biases and assumptions about sexual and gender minority patients.

-

Practice sensitive language.

Messick’s Framework

Assessment tool validation was performed through the five-step framework proposed by Messick,14,15 consisting of three major components of content, construct, and criterion-related validity, as described by Hamstra, et al.16 Five steps of the framework include content, response process, internal structure, relations with other variables, and consequences.17

Content analysis was comprised of developing the test questions correspondingly with Constructing Written Test Questions for the Basic and Clinical Sciences by National Board of Medical Examiners,18 and having the questions presented to a population that does not have formal training on the topic to provide unbiased input on improvement of the evaluation tool. Response process analysis consisted of recruitment of nineteen resident physicians to take the pretest, complete the assigned curricula, and lastly to take the posttest. Internal structure was examined through calculation of inter-rater reliability, item difficulty, and item discrimination. Relations with other variables was investigated through paired t test for comparison of pre and posttest results., as well as inspecting the data based on resident training level. Lastly, consequences were studied through attempting to determine the impact of the assessment tool on the participants.

Results

The results of this study are presented according to Messick’s framework, similar to other tool validation studies.19,20

Content

Test questions were developed in accordance with guidelines detailed in Constructing Written Test Questions for the Basic and Clinical Sciences by National Board of Medical Examiners.21 As stated previously in methods, Bloom’s Taxonomy was considered when adopting objectives in accordance with having questions that require lower-order thinking skills, such as “remembering” and “understanding,” as well as questions that require higher-order thinking skills, such as “analyzing” and “evaluating”.22 For instance, questions were included to assess the lower levels of cognition, such as defining fundamental terms in GAC. Additionally, questions of higher-level of cognition, such as proposing an improvement to a patient chart summary, were also included in the assessment. In a study performed by Qadir, et al, authors noted that developing curricula that allows for evaluation of students’ cognition in all levels in accordance with Bloom’s Taxonomy will allow for higher rate of success amongst students of all levels of knowledge on the assessment.23 Therefore, including questions that attempted to target all levels of cognition was of paramount importance as the tool intends to be versatile for novice and experienced learners.24 All questions in the assessment tool are mapped onto Bloom’s Taxonomy in Table 1, to demonstrate how these questions correlate with the different Bloom’s Taxonomy levels. Using Bloom’s Taxonomy to formulate the questions for this assessment might further promote validity for the content of the assessment tool under Messick’s Framework.

To ensure the content alignment and technical quality of the evaluation questions (Appendix A) they were presented to 8 medical students at Harvard Medical School. These students were not part of the exercise itself. The students represent a population that does not have formal training on the topic and who can therefore provide more objective data on improvement of the evaluation tool.25 They were asked for their understanding, opinions, and recommendations on the set of questions prior to finalization of evaluation method.26 The evaluation questions were reviewed and approved by all co-authors. Questions included multiple-choice (3 questions), select all-that-apply (6 questions), true-false (5 questions), and open-ended (1 question) (see complete instrument in Appendix A).

Response process

Nineteen resident physicians agreed to participate in this study from June-July 2023. Massachusetts General Hospital residents from the departments of medicine, psychiatry, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, and surgery were recruited through purposeful sampling. Participants were asked to take the 15-question pre-test. Then, they were asked to complete the Sexual and Gender Minority Terms and Concepts, Sexual and Gender Minority Health Inequities, Implicit Bias and Power Imbalances, and Sensitive and Affirming Communication lessons through the Harvard Medical School’s Sexual and Gender Minority Health Training Modules course. These four lessons were chosen as they addressed the main objectives of the assessment. After the modules, participants were asked to take the same test as they took prior to the lessons.

Our specific sample may have a remarkable impact on the obtained results. The quality and quantity of participants may have a prominent impact on the results.27,28 If this study is performed with a similar sample size that is of similar backgrounds as the residents at MGB, we would anticipate obtaining similar results to this study. The reason is that this study attracted trainees who were interested in the topic, who may have a higher level of knowledge than the rest of the resident pool due to the nature of their interest. If this study is performed at a similar healthcare facility as a mandated practice, it would include residents who may or may not be interested in the topic, hence may or may not have a basic foundational knowledge. In this instance, I would suspect the pretest scores to be lower than our sample, and the post test scores to be similar, as we would anticipate the participants to retain a notable amount of knowledge from the extensive module that is recommended through his study. With regards to sample size, it may be harder to predict the possible change in results depending on the size of the sample. However, with a larger sample size, we would anticipate means that are closer to the general population mean and anticipate smaller standard deviations than we obtained in this study.29

Internal structure

Internal-Consistency Reliability

Each item’s response was dichotomized into “correct” and “incorrect” answers. Interrater reliability was calculated using Kuder-Richardson (KR20) Formula as values are dichotomized.30 KR20 were calculated using Microsoft Excel and were notable for pretest KR20 of 0.62 and posttest KR20 of 0.52. Based on the KR20 values, there is moderate interrater reliability for the pretest and posttest amongst participants.

Item difficulty

Item difficulty was calculated using the total number of correct answers for each question, divided by the total number of participants. Difficulty levels were calculated using pretest and posttest results (Table 2). There was an improvement in performance for most questions after completion of the assigned modules. The questions that did not improve were already at 100% correct. Such improvement can signify reliability and validity of the assessment tool, as more difficult questions (lower percent correct) and easier questions (high percent correct) had an improvement in participant performance after completion of the modules.31,32

Item Discrimination

Item discrimination (Table 3) was calculated by subtracting the percentage of correct answers by high-performing students (top 5 students) by the percentage of correct answers by low-performing students (bottom 5 students). A higher item discrimination was observed in the pretest as compared to the posttest, which could signify the impact of the evaluation tool on trainee knowledge attainment.

Relations with other variables

General demographics

Participants included 5 (26%) surgery, 5 (26%) medicine, 3 (16%) psychiatry, 3 (16%) obstetrics and gynecology, and 3 (16%) pediatric residents. Eight (42%) residents were PGY-1, 6 (32%) were PGY-2, 5 (26%) were PGY-3.

Participants completed the pretest, modules, and posttest asynchronously with a provided honor code to ensure their answer submissions represent their own knowledge and not of others.

Pretest and posttest comparison

A paired t-test was performed to compare pretest and posttest results.33,34 Seventeen (90% of) residents demonstrated an increased posttest score. Two (10%) of residents did not achieve an increased score after completing the curricula, and no residents had a decreasing score (Figure 1). The mean for the pretest score was 10.26 and standard deviation 2.4. The mean for the posttest score was 12.68 and standard deviation 1.60 (Figure 2). Paired t-test for pretest and posttest results resulted in a 95% confidence interval of (1.81,3.03; P <0.001).

Mean difference is 2.42 (SD=1.26) and effect size is 1.92, demonstrating a large size difference between the pre and post test results.35

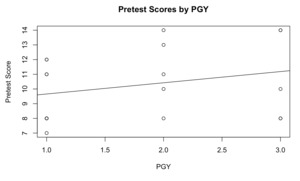

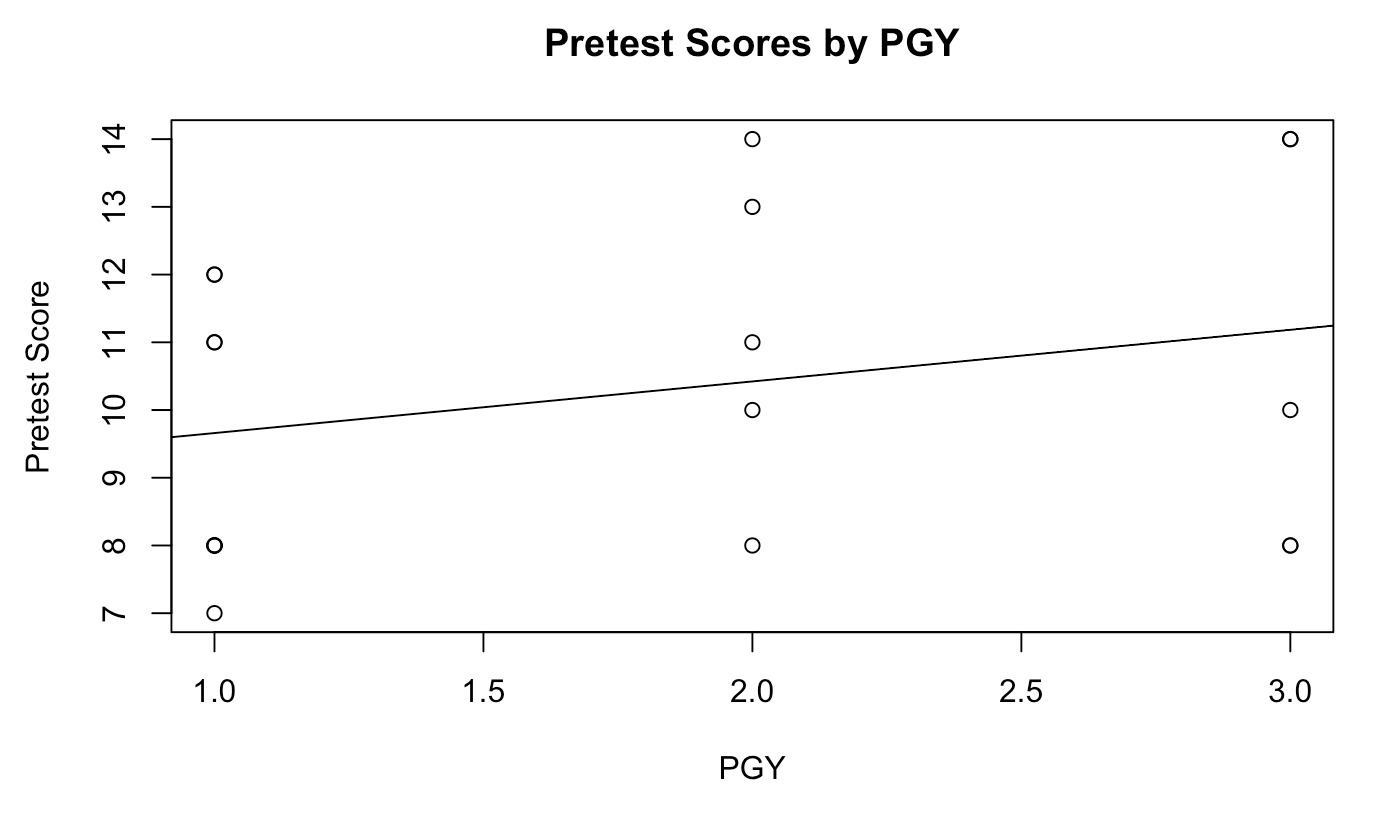

An important component of Messick’s framework is analyzing whether the tool provides a reasonable measurement of baseline knowledge in accordance with test takers’ level of training. To do so, we performed a simple linear regression using R-Studio to analyze the relationship between level of training and pretest scores. When plotting raw pretest scores by PGY years, the correlation was 0.27, with P-value=0.26 (Figure 3). The positive correlation is noteworthy for a relationship between level of training (PGY), and the outcome of the pretest. This relationship suggests that this tool may reasonably differentiate between novice and experienced learners,36 further validating internal consistency of the tool.

Looking through the lens of Bloom’s Taxonomy, as this this tool includes lower-level and higher-level of cognition questions (Table 1), it is of no surprise to observe that students with a higher level of knowledge and training (higher PGY level) did better overall, as they were able to correctly answer more of the higher-level of cognition questions as compared to students with lower level of training. In a study by Young, et al., the authors uncovered that physicians who have a higher level of knowledge and training were more likely to have a better written reports when utilizing Bloom’s Taxonomy to evaluate their clinical reports.37 Such findings are in accordance with the results of this study.

Consequences

The increase in scores for the posttest as compared to the pretest represents retention of knowledge through completion of the modules, further representing the importance of creation and completion of educational content on the topic of TGD care and sensitivity.38

Discussion

An imperative step in providing quality care is to better educate trainees on GAC, as well as cultural and sensitivity training on the topic of GAC. Curriculum enhancements are important in improving care provided to TGD patients.39 To evaluate trainees in a more systematic and standardized way, this evaluation tool has been prepared and validated. No other assessment tools on this topic have been validated to our knowledge.40

Tool evaluation was primarily achieved through paired t-test comparing pretest and posttest results. The t-test demonstrated a statistically significant improvement with a p-value of <0.001. No trainees had a decreased posttest score after module completion, which speaks to the validity and reliability of the evaluation tool. Furthermore, it is important for an evaluation tool to reflect additional training and differentiate between test takers of varying skill levels.41 In this tool, more senior residents achieved higher scores on the evaluation tool as compared to more novice trainees. Additionally, difficulty levels and item discrimination for each evaluation item have been provided, and institutions that decide to adopt this tool may decide to remove simpler or more difficult questions based on the needs of their individual goals and needs.

Our goal from creation of this tool was to enhance trainee education through evaluation and assessment. In light of that, our goal is to make this tool as widely accessible as possible for trainee education, as well as for tool enhancement. The first attempt we will make to address this matter is to pursue publishing in a peer-reviewed, open-access, free-of-charge journal. Additionally, we plan on making this tool available through MedEd Portal to reach a broader audience. Furthermore, we plan on reaching out to various medical schools, such as Harvard Medical School, to propose utilization of this tool in relevant courses if they see fit and reporting their feedback to us for enhancement of our tool. In addition, distribution can further occur through post-graduate training programs such as various residency programs across the country. We propose starting more locally at MGB through reaching out to various program directors and sensing whether they would be open to trying this tool with their residents.

Field of medicine is capable of adapting to current population needs by normalizing novel medical treatments and procedures. Such normalization would take form of patients seeking TGD and GAC as routinely and nonjudgmentally as they would seek care for hypertension, diabetes, or infections. We have seen such normalization in other fields of medicine. For instance, in 1980s, seeking care for Human Immunodeficiency Virus was considered to be taboo, while now it is much less stigmatized. While not a direct correlate to TGD care, such normalization is demonstrative of the field of medicine’s capability to adapt to current population needs. For institutionalization to take place, interventions at a national level are required, such as inclusion of TGD care questions on National Board of Medical Examiner’s three-step examination. Additionally, ACGME shall initiate requirements centered around TGD care for post-graduate medical trainee graduation.

Looking at the bigger picture of educating and assessing our trainees on the topic of GAC, we must address the need for creation of an assessment system. An assessment system includes various types and forms of assessment modalities that are utilized at various levels of the educational system, from the undergraduate, post-graduate, state, and national levels.42 Examples of different assessment modalities include written tests and quizzes, oral exams, observed interviews, and reflective essays. It is important to ensure the assessment system is varied and diverse to meet the needs and demands of all learners. Educators should also consider various forms of educational content delivery, and design specific assessment modalities for various forms of learning.43 For instance, in addition to lectures, simulation-based exercises, OSCEs, and observed interviews shall be utilized in educating trainees on the topic of GAC. For each specific modality, one or multiple forms of assessment should be considered and exercised to meet the demands of as many learners as possible.44

At an undergraduate level, assessment can take place in forms of written tests and quizzes, such as the assessment tool we have created in study three. Furthermore, undergraduate medical students can undergo OSCEs and observed interviews with simulated and standardized patients to demonstrate their basic proficiency in speaking with patients, as well as their understanding of fundamental medical principles. At a graduate level, resident physicians also require various forms to assess their knowledge and skillset. Assessment of resident physicians may continue to take form in written tests, such as the annual exam surgery trainees take known as American Board of Surgery In-Training Examination (ABSITE). Resident physicians also have competency requirements to meet. For instance, they have to demonstrate ability to perform a certain surgical procedure, such as a laparoscopic appendicectomy, prior to graduating from residency. At a state level, assessment takes form in state-specific licensure exams to ensure a standard level of knowledge on the topic of GAC. State licensure boards could consider completion of continuing education courses, with accompanied written tests, on the topic of TGD care to grant and renew medical and health professional licenses. To further solidify the importance and presence of this assessment tool, the assessment system should include the national system as well. Written test questions could be proposed to the National Board of Medical Examiners to be included in United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE), a three-step examination that medical graduates need to take to be able to obtain medical licensure. Additionally, ACGME shall initiate requirements centered around TGD care for post-graduate medical trainee graduation requirements at a national level. Addition of ACGME requirements would allow for expansion of trainee evaluation beyond knowledge—this would allow for trainee skillset evaluation that may have a more direct clinical impact.

Next Steps

An evaluation tool is developed in this study, and validity evidence is gathered using Messick’s framework. In this study, pre and post test results were used as comparative data. However, such data are collected in a non-clinical environment and further studies are needed to evaluate the clinical impact of the intervention. The next step would entail evaluating the influence of the assessment tool on trainee performance in clinical settings. In a study performed by Mecca, et al., the authors utilized a prospective cohort study to evaluate an interprofessional education intervention amongst primary care residents on the effects of polypharmacy.45 In another study by Kurashima, et al., the authors developed a rating-scale assessment tool to evaluate trainee education and patient outcomes during laparoscopic gastrectomy.46 Similar modalities can be used for interventions proposed in this study to evaluate patient outcomes as a result of implementation of various educational and assessment modalities.

Limitations

We believe this is a novel validated evaluation tool that is user-friendly, covers fundamental concepts, and is modifiable depending on various institutional goals and needs. However, this study is not without its limitations. As this study was validated at a single institution, there are risks for inherent bias. For instance, the resident pool at MGB may be different as compared to a resident pool in other healthcare networks in other parts of their countries and beyond as they are exposed to different resources, patient populations, and educational material. Furthermore, only interested residents were included in the validation study, which further adds selection bias to the study. In addition, a sample size of nineteen participants limits us from calculating inferential statistics on the tool’s validity and reliability, as well as limiting us from being able to make inferences about pre and post differences at the population level. Having said that, the goal of this study is not to make generalizable inferential statements, but rather to evaluate the tool’s quality from Messick’s validity framework. In order to produce results that are more generalizable, the findings of this study serve as steppingstones for creation of a future study with a larger participant pool.

To address inherent biases discussed in this study due to the focal sample from MGB, future studies can be proposed to enhance objectivity. A study that recruits trainee participants from various healthcare systems across the country will allow for a higher level of diversity in expert opinion and recommendations. Our participant pool will be further diversified and expanded to include resident physicians, medical students, and practicing physicians. Furthermore, as mentioned, our small sample size prevents us from drawing inferential statistics for our assessment tool.

Conclusion

An assessment tool is now available for educators to gauge and evaluate medical provider knowledge on the foundational concepts that are relevant to and impactful on care of TGD patients. This tool can be modified based on the needs of various programs. Although this study formulated the tool through resident physicians, it may be applicable to other healthcare areas, such as nursing aid staff, nursing, physical and occupational therapy, nutrition, and psychology.