Introduction

The typical trajectory for a leader in academic medicine is to continue to ascend the “academic ladder,” taking increasingly more senior positions. Often leaders do not leave those more senior positions until a higher-level position becomes available, they leave the institution, or retire.1–3 This all often occurs without a set period of time that they can hold the position, or a term limit.

Term limits are often discussed in the context of politics, with most political offices having some imposed limit on length and/or number of terms except most notably for Congress and the Supreme Court.4 Opponents of term limits in the political sphere fear issues such as inefficiency and inexperience from too much turnover and stagnation in the individual holding office as they await the end of their tenure. Proponents of term limits have pointed towards such potential benefits as increased turnover allowing for diversity and preventing long tenure from one person or political party.1,4–6 While the outcomes of term limits in politics have had varied results, they are also driven by elections which introduce an additional variable that is not present in most surgical practices.

Term limits have also been considered in business with similar goals in mind, particularly in those of increasing diversity and innovation.7 Evidence in this discipline is limited, however some studies have shown fewer new patents and citations from organizations with long tenures in their board of directors. This implies that there is less innovation when there is less turnover.8

The primary aim of this study is to assess the perspective of surgeons on leadership terms limits. Secondarily, the study aims to evaluate differences in this perspective amongst surgeons of varying demographic backgrounds.

Methods

A nationwide survey-based assessment of surgeons’ perspectives on leadership was performed. A list of possible survey questions was generated from interviews with 25 surgeons from different specialties and institutions. The survey was piloted among a different group of 10 surgeons and survey questions were modified based on the collected feedback. A final questionnaire consisting of 30 questions (25 multiple-choice; 3 open-ended; 2 Likert-scale) (Supplement), was emailed nationwide from November 1, 2022 - January 31, 2023, to surgeons from various specialties. The survey response tool was set up such that each participant was able to respond only once to the survey. All data was collected in accordance with the requirements of our Institutional Review Board.

Participation in the survey was voluntary, and no compensation was provided. Anonymity was ensured by not requiring any personal identifiers. Reviewers were blinded to the respondent’s institution. Participants were informed in writing that by answering the questions and returning the survey, they were providing and documenting their willingness to participate.

Only surveys with >80% of items completed were included in the analysis. Results were calculated based on the number of responses received to each individual question. Free-text responses from open-ended questions were independently coded and the resulting nominal data are presented as percentage of responses per category.

Statistical data was analyzed using SAS data analysis software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute®). The Chi-square test was used to measure the relationship between nominal scale variables. The Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used to compare ordinal scale variables. Statistical significance was accepted at p ≤ 0.05 and all tests were two-sided.

Results

Over a collection period of 3 months, 671 of 2360 surveys were completed (28.4% response rate). Both female [38.6% (259)] and male [52.1% (349)] surgeons participated in our survey. Other characteristics of our survey respondents are displayed in Table 1.

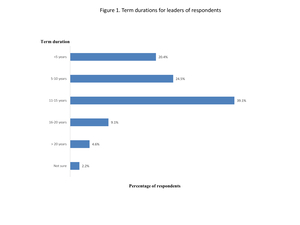

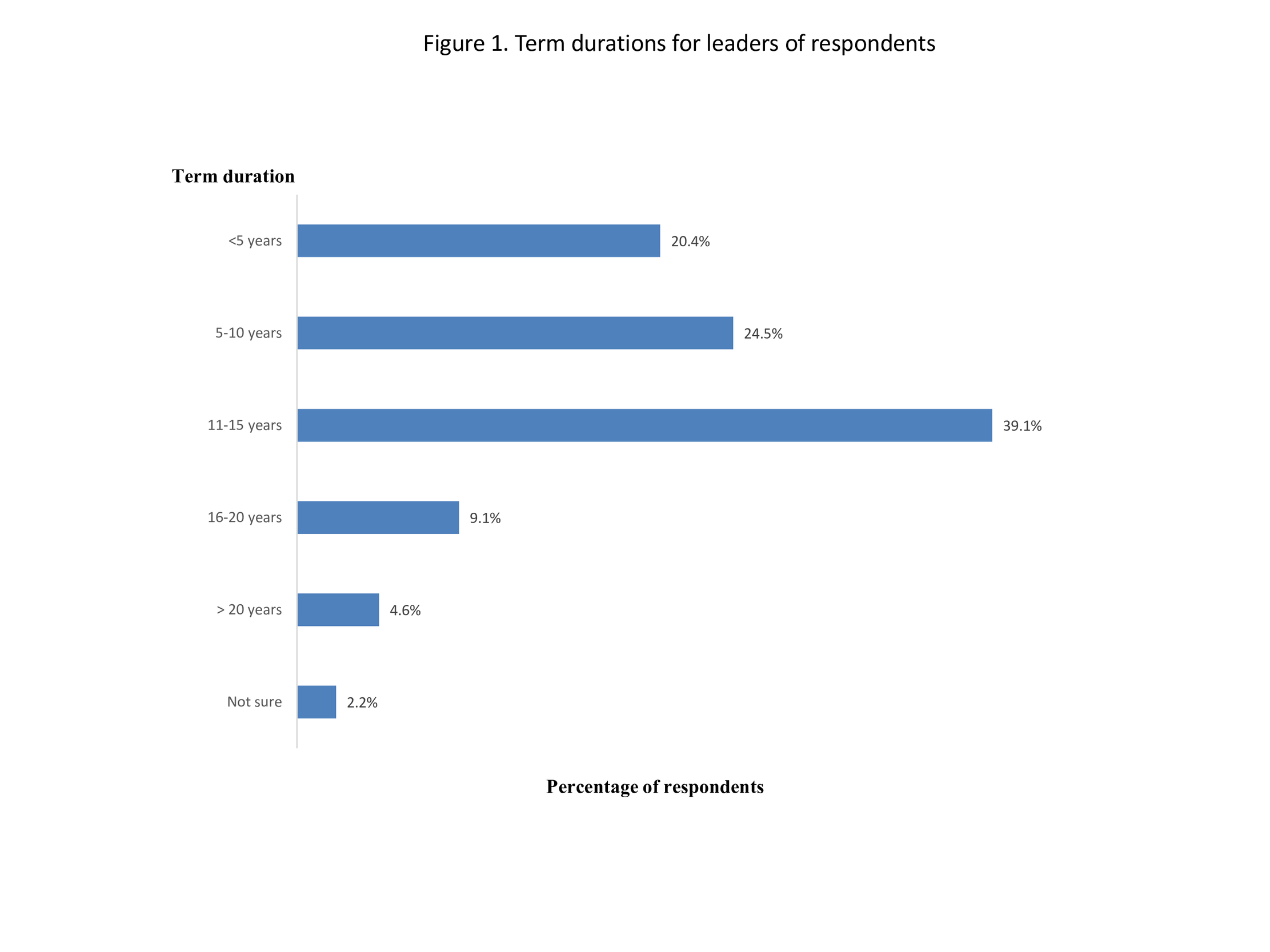

Respondents reported that most of their leaders have been holding their positions for a duration of 11-15 years (39.1%), followed by 5-10 years (24.5%), <5 years (20.4%), 16-20 years (9.1%), and > 20 years (4.6%) (Figure 1). Most respondents (84.1%) denied the presence of term limits, with only 4.6% of them reporting having leadership terms in their practice.

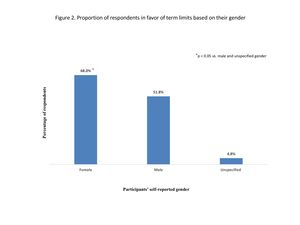

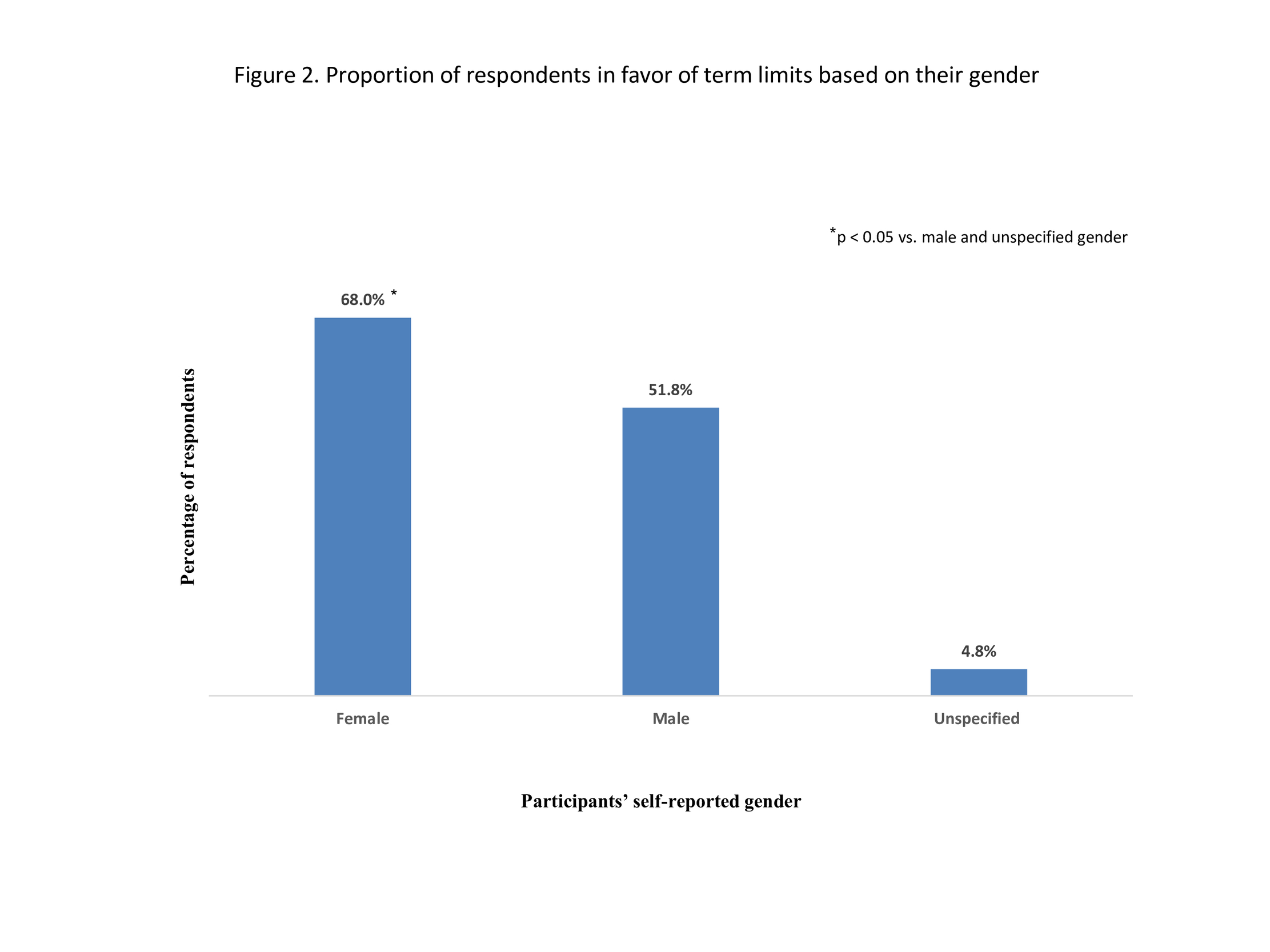

Over half of respondents (53.6%) are in favor of implementing leadership term limits, with 34.2% of them being against, and 8.2% remaining undecided. The proportion of female surgeons in favor of terms limits was significantly higher than males [68.0% (176/259) vs. 51.8% (181/349) respectively; P < 0.05] (Figure 2). Other demographic characteristics were not associated with significant differences in the favoring the term limits.

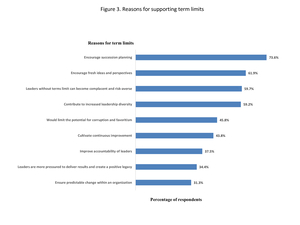

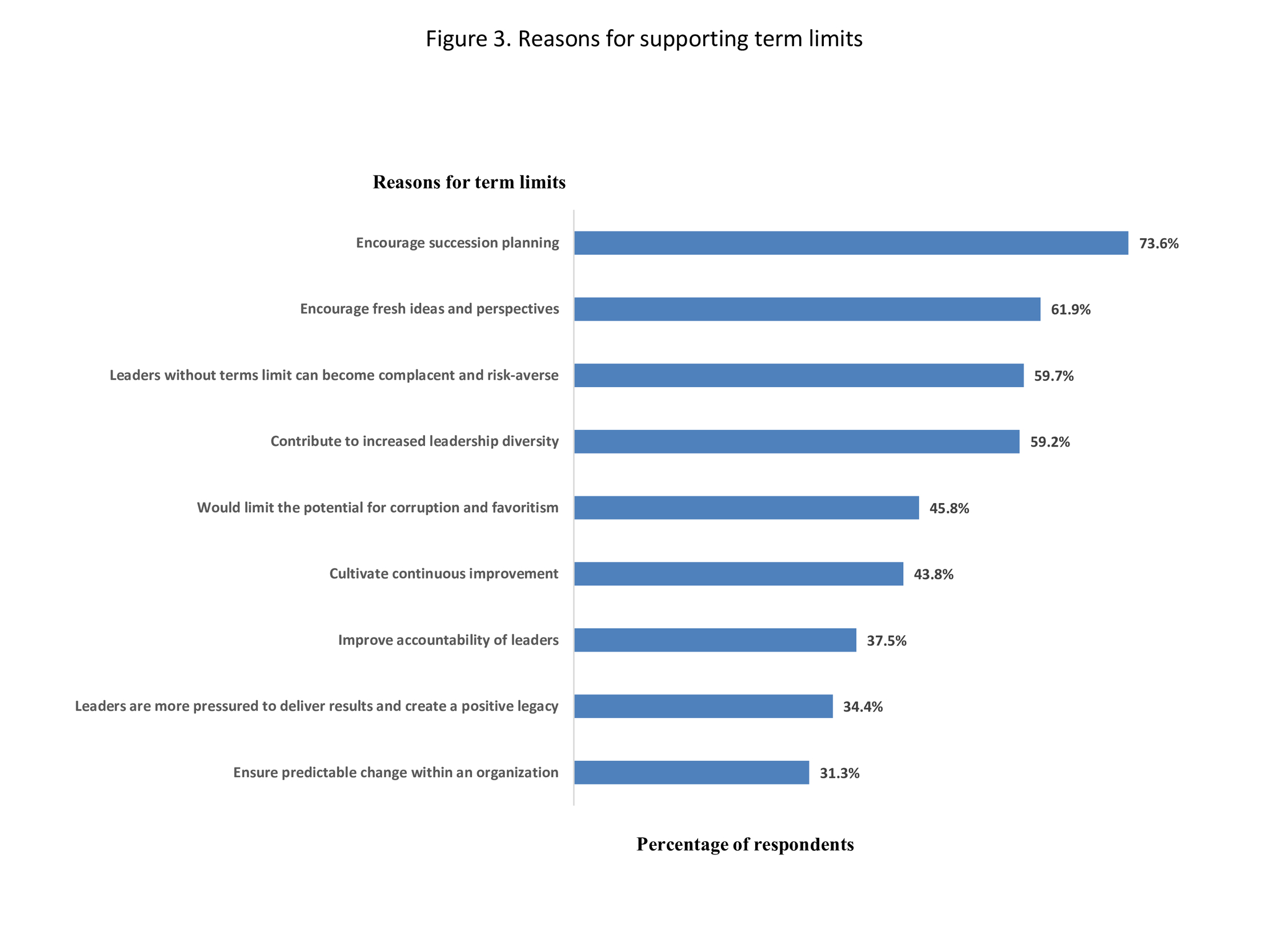

The primary reasons for favoring term limits were facilitation of succession planning (73.6%), encouragement of fresh ideas and perspectives (61.9%), avoiding leader complacency and risk-aversion (59.7%), and increasing leadership diversity (59.2%), followed by preventing corruption and favoritism, cultivating continuous improvement, improving accountability of leaders, pressuring leaders to deliver results and create a positive legacy, and ensuring predictable change within an organization (Figure 3).

Surgeons who were against term limits for their leaders consider that would be associated with disruption of stability and continuity of leadership within an organization (74.2%), high leadership turnover and staff burnout (58.1%), loss of institutional memory on policies, practices, and actions (45.2%), disincentivizing leaders to make uncomfortable changes and leaving them for their successors to deal with (41.9%), sufficient time for leadership development (31.0%), reduction of leadership engagement (29.0%), inability to appropriately evaluate leadership effectiveness (19.4%), reduction in mutual trust (17.9%), and increased recruiting efforts and costs (16.1%).

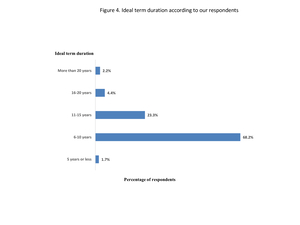

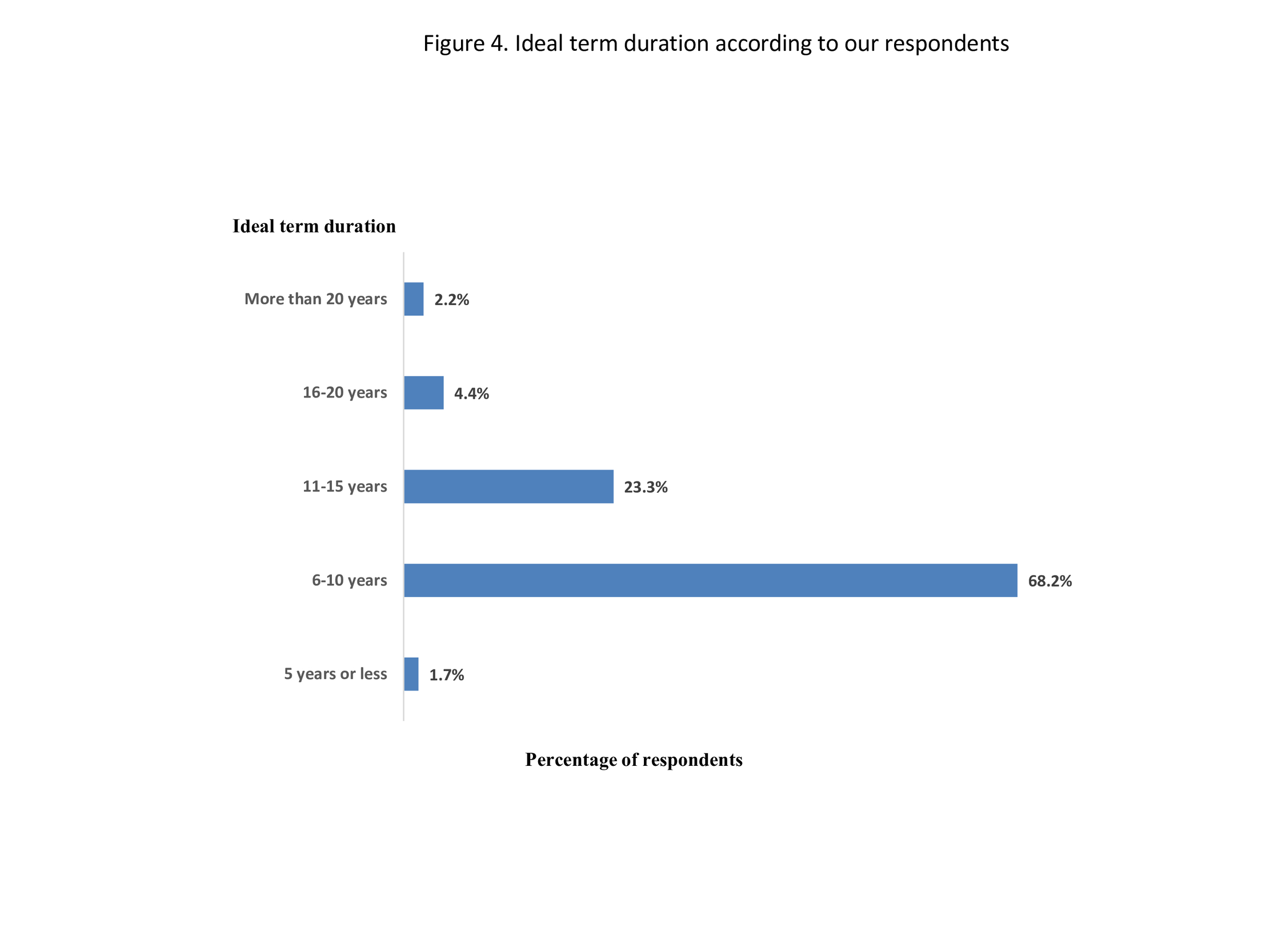

Most respondents (68.2%) believe that the ideal duration of the term would be 6-10 years, followed by 11-15 years (23.3%). (Figure 4).

Discussion

This study is the first to explore perceptions of surgeons on the implementation of term limits in leadership. We identified a lack of term limits in surgical leadership, with less than 5% of respondents reporting the presence of term limits in their practice and many leaders maintaining their positions for over ten years. A little over half of the respondents reported being in favor of leadership term limits.

Proponents of term limits pointed towards benefits such as creating opportunities for new ideas and avoiding leadership complacency. This must be balanced against concerns brought up by the opponents of term limits such as disruption of stability and loss of institutional memory. One way in which this can be achieved is by selecting an appropriate length of time for a term limit. The National Institution of Health (NIH) has enacted as 12-year term limit for lab and branch chiefs who oversee intramural research.3,9 This duration fits with the findings from this study with most respondents in this survey believing the ideal duration would be 6-10 years, followed by 11-15 years. Another consideration is the concept for flexible or informal term limits. This is the idea of, rather than instituting a limit at a set number of years, the term would be flexible depending on the needs of the position itself and the age and experience of each leader.10 An additional concern is that some departments may not have the pool of leaders that may want to ascend and that creating stringent limits could result in leadership gaps. An informal process could address this as well. Some argue that academic medicine already has a version of the informal term limit with the process of the 5-year review. This process exists in a number of academic medical centers, where leaders undergo internal and external review every 5-years to determine if leaders should continue in their position.11 Further study into the utility of 5-year review is necessary to determine if this functions similarly to a term limit.

Proponents of term limits in this study also responded favorably to a potential benefit in increasing diversity. Additionally, we found that a significantly greater proportion of female surgeons were in favor of term limits when compared to male surgeons.

Term limits at the NIH and in other fields have been enacted with the purpose of improving diversity.1,9 Surgery has been diversifying but this has not translated into the highest ranks of leadership. Recent study found that more males than females occupied leadership positions at all levels. Only 8.9% of all leaders were Underrepresented in Medicine (URiM). Interestingly this study also found that female and URiM leaders were clustered into roles such as vice chair of diversity, equity and inclusion or vice chair of faculty development. Positions that they posit may not have as much upward mobility to department chair.12 While this lack of diversity in senior leadership is likely multifactorial, an intentional strategy such as imposing term limits could help create opportunities for diverse leaders to ascend.1,13

This study is limited by its sample, with a large proportion of respondents coming from academic centers in the Northeast or Midwest. The generalizability of this data to community or rural settings is limited in this case, however we believe this study contains important insights for leadership of academic surgical practices. Future studies are necessary to evaluate outcomes such as leadership diversity and surgeon satisfaction in practices with term limits and compare to those that do not have term limits.

Conclusions

Term limits are not commonplace in surgical practices but about half of respondents reported favorable opinions about instituting term limits for surgical leadership. Term limits may be considered to create opportunities for diversity and innovation but should be cautiously approached with consideration to avoid disrupting stability and institutional memory.

Disclosure

This research did not receive any specific grant funding from agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures to declare.

SAAS reference

This study was presented at the Society of Asian Academic Surgeons (SAAS) 8th Annual Meeting, September 14-15, 2023, Baltimore, MD, USA.