Introduction

ChatGPT is a language model developed by OpenAI. It is designed to interact with users by generating a text response based on the input it receives. It is considered a large language model (LLM), meaning it has been trained on a vast amount of data, allowing it to understand and generate human-like text responses.1

ChatGPT has the potential for a paradigm shift in healthcare education, research, and practice. It can improve scientific writing, research, healthcare practice, and education.2 ChatGPT’s academic prowess has already been tested on various medical examinations, with mixed success.3–6 To date, there has not been an application using ChatGPT to perform a surgical primary exam, nor has ChatGPT been used in any Australian medical examinations.

The Generic Surgical Sciences Examination (GSSE) assesses understanding and applications of the surgical sciences of anatomy, pathology, and physiology.7 It is designed to provide a sound basis for surgical training and subsequently is a prerequisite to passing in Australia before the commencement of surgical training. It is set over two days and contains 185 multiple-choice (A/B/C/D/E and true/false) 20 and anatomy spotter questions. The anatomy section comprises 50% of the overall mark, whilst pathology and physiology are each worth 25%. A pass mark is determined by the training college for each sitting, and it is adjusted to account for differences in exam difficulty.7 A candidate must pass each individual section (anatomy, physiology, and pathology) and pass the examination overall.

Our study aimed to determine whether ChatGPT could pass the GSSE.

Methods

The popular large language model ChatGPT-4 (OpenAI; San Francisco, California) was used in this study. It processes text input using self-attention mechanisms and a massive training data volume to output natural language responses. It is a server-based service that lacks the native ability to browse the internet, as opposed to some other chatbots that do have this ability. Hence, responses to user queries are generated in situ, using abstract associations between query words/phrases (termed “tokens”) in the neural network.

The Royal Australian College of Surgeons (RACS) provides 5179 practice questions through its publicly available database for candidates to practice in preparation for the GSSE. 100 questions were randomly selected using computer pseudo-randomisation to replicated the weighting given to anatomy, pathology, and physiology - 50, 25 and 25 questions, respectively. The spread of questions within each section was distributed based on the spread demonstrated within the practice database - for instance, if 10% of the physiology section in the database was on the topic of cardiovascular physiology, then 10% of the physiology questions posed to ChatGPT were on cardiovascular physiology. Questions were input into the chatbot with minor modifications of the original question prompt (see supplemental material for example) and using without-answer options.

Question responses given by ChatGPT were codified into a binary labelling system to denote correct (‘Y’) or incorrect (‘N’) Chat-GPT answers. An example of three sample questions and ChatGPT responses are provided in the supplementary material. This was done regardless of the justification for the answer and solely based on whether the chatbot’s answer aligned with the answer determined by RACS. The answers provided by RACS were all presumed to be correct.

A deductive analytical approach was applied, guided by pre-established categories of medical topics, including anatomy, pathology, and physiology. Wilson Score Intervals were used to compute 95% confidence intervals for overall and category-specific accuracy. Statistical significance was assessed through one-sided binomial tests, comparing the observed performance against defined pass marks. Given that the pass mark varies between exam sittings due to its dependence on the scores of the cohort’s scores, the pass marks from the October 2022 sitting were used since this was the most updated data at the time of analysis.

Ethical approval was not required for this study as per the guidelines of the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia, since it did not involve human participants, personal data, or any intervention. The study exclusively analysed the capabilities of artificial intelligence in answering standardised test questions, exempting it from ethical review.

Results

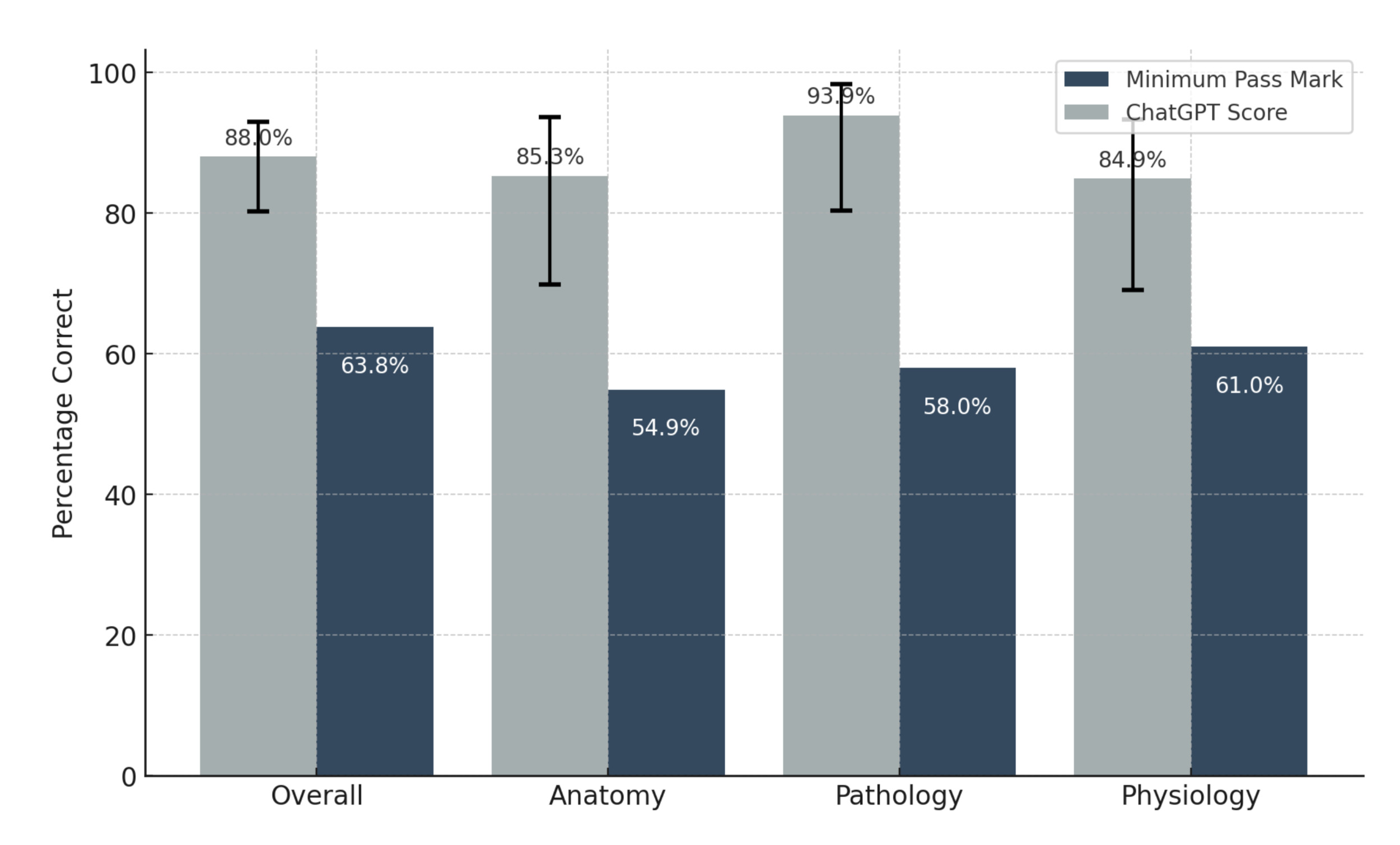

ChatGPT’s accuracy in answering GSSE questions was 88.0% overall and 85.3%, 93.9% and 84.9% for anatomy, pathology, and physiology, respectively. There were no indeterminate responses given by the chatbot. The minimum standard pass mark for the October 2022 sitting of the GSSE was 63.8% overall and 54.9%, 58.0% and 61.0% for anatomy, pathology, and physiology, respectively. Figure 1 demonstrates the pass marks and ChatGPT scores. ChatGPT attained scores that surpassed the minimum standard overall and section pass marks for the October 2022 sitting and showed statistically significant differences overall (p < 0.0001), as well as in the anatomy (p < 0.0001), pathology (p < 0.0001) and physiology sections (p = 0.0028). Table 1 outlines the scores and 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

In our study, ChatGPT performed significantly higher than the required pass mark for the multiple-choice questions on the GSSE. These findings exemplify the impressive capabilities of a large language model to recall and apply medical expertise across the topics of anatomy, physiology, and pathology. Literature already exists regarding the benefits demonstrated by using artificial intelligence in medicine and surgery, including diagnostics, risk prognostication, medical and surgical treatments, and patient counselling, among other implementations.8 Our study corroborates these documented benefits.

Compared to traditional search engines that compile and present links requiring further interpretation, ChatGPT provides immediate, direct answers drawn from its vast integrated knowledge base. This distinction is critical in surgical settings, where the ability to quickly access and synthesise accurate, relevant information can be lifesaving. In the context of surgical examinations and practice, the efficiency of an AI system like ChatGPT in providing precise information without the need to navigate through multiple external sources becomes a significant advantage. Furthermore, ChatGPT’s ability to contextualise its responses based on the specific input it receives allows it to offer more tailored information, which is highly valuable in the nuanced field of surgery, where specific case details often dictate the required knowledge and approach.

It is worth noting that our results are tempered by several notable limitations that must be critically considered. Firstly, whilst our sample of 100 questions was sufficient to prove with statistical significance that ChatGPT could pass the GSSE, it is still a relatively small proportion of the full GSSE. A larger sample size across a broader range of topics would confirm ChatGPT’s knowledge across all components of the examination. Additionally, our study focused solely on the multiple-choice component of the examination. The actual GSSE contains anatomy spotter stations, as well as short answer questions - of which these critical elements were not evaluated. A large language model with current levels of capability may face challenges in identifying photos of gross anatomic specimens.

Additionally, large language models are known to generate confident but factually incorrect statements and fabricate evidence—a phenomenon charitably known as “hallucinations”.9–11 They may also perpetuate pre-existing societal biases instilled in their training corpora.11 Without robust fact-checking and careful human oversight, misinformation like this can have potentially disastrous outcomes in the healthcare domain, where patient safety is paramount.

Furthermore, the use of AI models in healthcare raises significant ethical considerations. Should AI find itself immersed in day-to-day clinical activity, there are concerns regarding data privacy, bias, and lack of transparency in these “black box” systems.8 The outputs of AI lack the emotional intelligence, empathy and human touch that is paramount in-patient interactions. As AI technology becomes more powerful and capable, we must be cautious of over-reliance on AI at the expense of eroding human clinical judgment and decision-making skills. AI must be used to augment human care, not substitute it. It is vital for a robust ethical and governance framework to be established to mitigate these complex issues.8

Lastly, it is essential to acknowledge that medical examinations, such as the GSSE and later fellowship examinations, assess many vital qualities beyond knowledge recall - such as communication skills, professionalism, ethics, and higher-order cognitive abilities that ChatGPT cannot yet replicate. Whilst AI will continue to expand and complement some aspects of medical training and healthcare delivery, we need to continue investigating its strengths and limitations so that its implementation does not come to the detriment of our human-centric healthcare delivery standards.

Conclusion

This study confirms that ChatGPT can achieve scores surpassing the minimum standards required to pass the multiple-choice section of the GSSE. Whilst AI has progressed rapidly in recent times, these results should not be over-generalised. Surgical entrance examinations encompass many other vital components that were not tested in our study. A prudent, evidence-based approach is necessary to delineate the strengths and weaknesses of the use of AI in healthcare so that we may harness its capabilities without adversely affecting patient safety.